DSQ blog

The Sweet Spot – music and sport part 2

Serena Williams on form… again.

With Wimbledon in the offing, I can’t resist continuing the tennis/sport/music theme from the previous post.

I have always seen parallels between music and sport – I admit to being biased towards bowed string playing, tennis, and football here – but actually pinpointing the similarities has produced a list the length of which has surprised even me.

Trajectory. Momentum. Movement. Awareness. Preparation, swing. Placing. Watching. Receiving. Listening. Movement. Attack. Weight. Agility. Goal. Target. Live – in real time. Warm up. Nerves. Euphoria. The psychology of confidence. Doubt. Doldrums. Team work. Social side. Morale. Accuracy. Improvisation. Adjustment. Frustration with the manager/conductor. Uplift of the inspiration of other players. Analysis. Focus. Muscle memory. Balance. Preparation – mental and physical. Unrepeatable event. Importance of the crowd/audience relationship. Supporters. Commentators. Critics. Play. Fun. Importance of heroes of the players in their minds. Stamina. Pacing. Speed. Skill. Technique. Training. Parental support. Psychology. Mental attitude. Collective awareness and understanding. Visualisation. Presentation. Performance. Imagination. Dreaming. Physicality. Adrenalin. Post mortem. Pacing. Build up. Release. Relaxation. Suppleness. Flexibility. Fluidity. Strength. Training. Balance. Timing. Set pieces. Strength. Softness. Resonance of playing objects. The bounce (ball/now on string). Sweet spots. Finding the most efficacious point of contact. Working with the tightness/pressure of the ball is like working with the tightness of a string to transfer energy and create momentum in creative ways. The visceral experience of responding to kinetic energy and managing latent energy. Substitutions. Athleticism. Reaching – calculated and instinctive – for the ball, for a note. Concentration. Beauty – of action, movement. Intention.

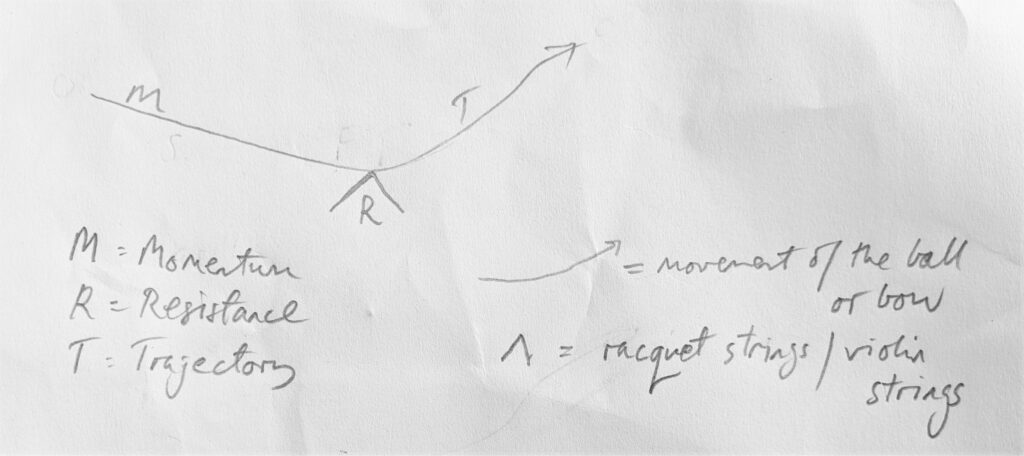

This list without doubt opens up all sorts of possible avenues to pursue, but for the moment, perhaps I can summarise it all in the following drawing that I came up with after considerable thought on what happens when sports people make contact with the ball and likewise what happens when string players produce notes:

(Looking at this, you can see, I am sure, how very wrong it is to label musicians as arty-farty and without any scientific aptitude.)

The drawing is of course simplified but I’m going with the maxim that there is a beauty in simplification. In particular, what it doesn’t show is where the real skill of the event takes place – what happens at the point of contact (R) where there is both mastery and mystery – mastery in the sense of understanding exactly what will happen if the ball or string is approached in a certain way (speed, weight, angle) – and mystery because there are so many indefinable factors too, like instinct, the nature of the moment of contact, the way that imagination is transferred from thought into physical action.

These videos show in slow motion the point of contact where ball meets racquet and bow strokes string. There are differences of course but the similarities are remarkable, not least the way that bow string and racquet strings are set into motion by the contact. The action and nature of the bow and the construction of the racquet in facilitating friction and tension is a huge subject in itself, which I won’t even attempt to launch into here, but they are hugely significant factors.

When a pupil informs us that he or she won’t be attending the next music lesson because they are in a hockey match, or sports match of any kind, it’s tempting to be disappointed and even disapproving. (How could anything be more important than their violin lesson?!) But we can’t; sport is good for their health, and complements their music studies in more ways than they probably realise. I have often thought that I’d like to be out there on the pitch too, in the fresh air, enjoying the game, bizarre as that would be in reality – apart from anything I might inadvertently crush someone half my size. The last time that I played cricket was at a father’s match against my son’s team about twenty years ago. I started getting into my stride at the crease, holding the bat one handed like a tennis racquet, swatting the balls away playfully. I was a bit of an embarrassment treating the opposition like that and my son disowned me, temporarily.

There are so many aspects of sporting performance that are similar to musical performance. Rather than talking about it, here are some videos to enjoy. I hope you can see the parallels. If not, I have totally wasted your time, for which I apologise.

David Oistrakh performing Tchaikovsky:

Pete Sampras and John McEnroe – two tennis artists

A collection of football volleys – impeccable timing and execution

Alina Ibragimova playing Saint-Saens

“Oh, I say!” Music and sport part 1

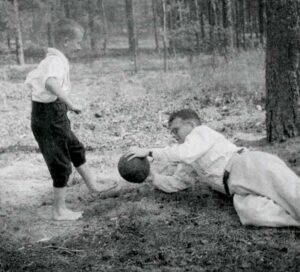

Mozart enjoyed a game of skittles, and Shostakovich loved football to the extent that he qualified as a referee. He is seen here playing football with his son Maxim. He supported Leningrad Zenit (now Zenit St Petersburg), frequently going out of his way to attend their matches. According to Maxim Gorky ‘he was a rabid fan. He comported himself like a little boy, leapt up, screamed and gesticulated’ at matches. Generally thought to be introverted and depressive, it is good to hear that Shostakovich found a way of releasing tensions, even if his interest in football is also inextricably linked with the state approval of the game as being beneficial for society. As ever with Shostakovich, it is never a simple story.

I think it is undeniable that he translates some of the energy and fun of football into his music at times. This is arguably evident in the 3rd string quartet’s first movement, but even more overt in this piece, ‘Football’ from ‘Russian River’ Op 66.

Without doubt there is a parallel in his music with the extremes of euphoria and despondency that players and fans feel after an important match.

Shostakovich at a football match

Shostakovich at a football match

I don’t know if Shostakovich played tennis. He may well have been persuaded to play a set or two with his friend Benjamin Britten on the grass court at Britten’s Red House home when he visited. Britten was a very keen tennis player, and it seems that he was rather intimidating on the court, as he could be when making music with others.

Benjamin Britten and Frank Bridge composer, teacher of Britten and fellow tennis enthusiast.  Britten (left) on the court at The Red House, his home in Aldeburgh.

Britten (left) on the court at The Red House, his home in Aldeburgh.

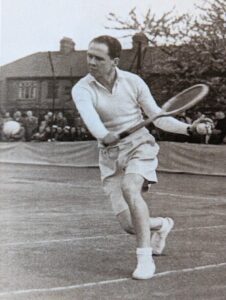

My violin teacher, Colin Sauer (first violin of the Dartington String Quartet, renowned for their performances of Shostakovich and Britten quartets, amongst others), was a superlative violinist as well as an extremely gifted sportsman – tennis in particular. The war intervened just as he was heading for Junior Wimbledon – he was being coached by Dan Maskell, who later became the strawberries-and-cream-mouthful voice of Wimbledon, with his trade mark “O, I say!” when a player’s shot impressed him. Colin would have given Britten some difficulties on court, for sure.

Colin Sauer wielding his Maxply. (Photo included courtesy of the Sauer family)

Colin Sauer wielding his Maxply. (Photo included courtesy of the Sauer family)

This picture shows how close, in a way, the tennis racquet is to a violin bow – it’s spring and tension, and how it is wielded creatively for its impact with the ball. There is artistry in both. There will be more on this subject in the next blog.

Colin was the inspirational conductor of a youth orchestra in Devon in the 1970s. Along with his excellent musical tutelage, his anecdotes during rehearsals were legendary. I remember him recounting a first hand incident when Toscanini implored the musicians he was conducting to ‘”Play louder….louder…. LOUDER!!”. The stories were certainly a helpful pause from his exacting and inspirational musical demands. I’m sure he was aware of the benefits of some light relief during rehearsals although there’s no doubt that he loved to hold court too.

The orchestra residential courses always had a table tennis competition built into the timetable. The winner faced the ultimate challenge of playing Colin in an entertaining ‘demonstration’ match that as far as I’m aware always resulted in a slaughtering by Colin.

Perhaps it is not surprising that I was completely obsessed with tennis in my early teens. I used to fantasise about Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors or Chris Evert driving by on their way down to holiday in Cornwall (on their own, not all together), spotting me practising on court and offering to give me a game. It never happened. They drove on by, the heartless people.

Fortunately for me, when Colin and his family came to visit my family home on a sunny summer day I persuaded him to have a ‘knock around’ on the tennis court there. He had a heart condition that was causing some concern but he agreed to a short session and I thought that I would go kindly on him rather than be the cause of his demise.

I could tell from the outset that everything about his game exuded class – footwork, timing, and a fluid grace in his playing style. We knocked up for a bit and then played a set. I was annihilated. As ever, I learnt a lot.

Like Colin, who tended to time rehearsals around important tv coverage of Wimbledon or a cricket test series, DSQ’s Mary likes to keep abreast of how matches are going. How she manages to remain focused in rehearsals with this going on is a marvel; how the rest of us do too is even more of a marvel.

Vicky enjoyed playing netball, hockey and tennis at school, and still loves games, particularly Scrabble with her family. Lindsay’s preference over almost everything else in life is to be swimming in the icy cold water of a river or feeling at one with the sea. We all have our particular forte, and the odd piano too.

Next subject: The Sweet Spot – Sport and music part 2

The thrill of a trill

Like that moment of hearing the first cuckoo in spring or the long awaited arrival of the first house martin, live music making is returning after the long sabbatical due to the pandemic. It will be very good to resume this unique communal experience, which has been much missed by audiences and musicians alike.

Along with a profusion of flowering plants, the glorious abundance of birdsong and the visits of multitudes of birds to our birdfeeders all indicate that spring has well and truly sprung.

Looking after my grandson recently, on our way from the play park we were entranced by the singing of a blackbird close by.

Birdsong has often been an inspiration for composers, not least Mozart, who even had a pet starling for a while. Musical trills (rapid alternations between two adjacent notes) have, without doubt, strong associations with birdsong.

While rehearsing Mozart’s quartet K. 464 (which we will be performing in our forthcoming concert series), each time we have played a particular passage in the slow movement, my colleagues have in turn expressed surprise at hearing me indulge in a trill. One of them even said that she assumed I was “at it again, adding extra ornamentation.” For once, this wasn’t the case; Mozart indicates a trill in the viola part alone while nobody else is at it.

Often ornamentation such as this is in the first violin part in music of this era so for the viola to be given a share of the extra embellishment shows how Mozart viewed music making as fundamentally collaborative and communal. I suspect that when he and his friends played chamber music together there was considerably more embellishment than we see actually written in the score, often no doubt resulting in hilarity. Oh to be a time-travelling fly on that wall!

There is a particularly wonderful example of how emotionally telling a trill can be in the slow movement of Mozart’s last piano concerto, No 27 K. 595 https://youtu.be/DKZ3rqmYJ38 The passage is between 7:08 and 7:28 – not in the solo piano but first in the violins and then the oboe – a true sharing, and somehow all the more effective because of where it happens in the structure of the piece – where the coming together of all the constituent parts is most intimately and tenderly expressed.

For a while a particular Mozart piano concerto will be my favourite, but then I hear one of the others again and the hierarchy is disrupted. It’s a rather silly game. You may recognise it from your own experience of listening to the music of various composers and artists – for example, Bob Dylan’s songs, or Joni Mitchell’s, or Schubert’s, or Bacharach’s, or Ian Dury’s etc etc.

Mozart’s 21st piano concerto (K. 467) was on the radio recently. I listened, transfixed by it – particularly the first movement. Somehow, despite having studied the work for music O level, it still brings on the goosebumps. Of all of his piano concertos though, I certainly couldn’t do without No. 27 and not just for the thrill of the trills.

Next blog subject: “Great shot!” – music and sport.

Pictures by AG

The surprising joy of street furniture

Hello from the Divertimento String Quartet bunker. We very much hope that our friends and followers are keeping well amidst the current restrictions and difficulties.

We are planning on a return to concert giving as soon as we possibly can – hopefully in May. Details will be announced soon. We are very much looking forward to performing Shostakovich’s 3rd quartet and Mozart’s K.464.

The insularity of lockdown is challenging in several ways. I would however like to highlight a curious symptom of lockdown that is rarely if ever discussed, which is a shame because it has the potential to bring much benefit to our experience of lockdown. I am sure it is something that many of you will have noticed; namely an increased awareness of sounds.

Sometimes a sound that would have gone unnoticed before comes to the fore in a surprisingly vivid way. I have found myself being enthralled, amused, bemused and amazed by such sounds, many of which are very quiet. Often they are completely new and original. Even something as mundane as pulling tea bags out of a shelf becomes a remarkable sonic event:

I have discovered the surprising joy of street telecommunications furniture. Out walking along a street normally plagued by a stream of noisy cars but becalmed in lockdown, I became aware of a hum emanating from this box:

(Please note the other piece of street ‘furniture’ here, which it has to be said is a load of rubbish in comparison.)

And here is the veritable symphony of sound that I heard – headphone listening is advisable for full enjoyment:

Yes, it is a very quiet symphony but none the worse for that.

Some sounds have arisen during the routines in lockdown. I will let you guess what this is.

Here is a clue:

Several composers have incorporated the sounds of everyday life in their compositions, from Bach’s donkey in Cantata BWV 201 (audible around 2:00 in this recording) https://youtu.be/9RnmGBgHsQ4 to the inclusion of recordings of birds in Rautavaara’s Concerto for Birds and Orchestra “Cantus Arcticus” https://youtu.be/HLjXgV-Mhp0 . I also recall the very effective inclusion of children’s voices in Supertramp’s ‘School’ https://youtu.be/mYP7RpZqAs8 .

There are without doubt countless other examples in classical and popular music, and who knows what everyday sounds percolate into music, unknown to both composer and listener. Please feel free to comment with your own favourite examples of everyday sounds in music and add links if possible.

The sounds that we hear in lockdown can intrigue and entertain us, for sure. They don’t need to be translated into a formal musical context to become meaningful. They draw us into a fascinated contemplation of the phenomenon of their existence and of our perception of their existence.

It is now just under a year since we posted an arrangement of a Bach prelude for violin and viola during the first lockdown. It seems appropriate to add another one during the current lockdown and we hope that you enjoy it. It is a cliché to say it, but it’s true: Bach’s music is timeless, ceaselessly flowing like his name. (Bach = brook or stream in German). Of all composers he is arguably the most cosmic – and yet he could also revel in the comic braying of a donkey. The mundane can also be priceless.

Warmest wishes to you from Andrew, Lindsay, Vicky & Mary

Unbroken Peace

I have heard it said that the music of Haydn and others from his era is like ornamental porcelain. Quite what is meant by this, I am not sure. Maybe it is a compliment; I suspect not. I think the implication is that it is a thing of beauty but rather distant and somehow rather fragile and passionless.

From the musician’s perspective, Haydn’s music is supremely crafted, as is the very best porcelain of this period, with classical proportions, but what makes it so rewarding to play is the way the parts balance, there is an astoundingly sophisticated awareness of texture, and the emotional content is so varied, from melancholy to silly humour. His music – his quartet music at any rate – is clearly written for friends and emanates from a warm heart.

Eirene, goddess of peace. Meissen (Michel-Victor Acier). The Hermitage

This stunning Meissen figure was made in or around 1772, the same year that Haydn wrote his ground-breaking but not porcelain breaking Op 20 quartets.

Eirene, the Greek goddess of peace, stands elegantly – almost provocatively – atop various symbols of war that have been immobilised by her, presumably. The ancient classical allusions are very clear but this is a decidedly modern take on the subject, and unmistakably of this neoclassical period of European art. (There is no doubt a potentially lively feminist response arising from this depiction of Eirene, and on the origin of the subject. An online group debate could be fun.)

Can we see a link with Haydn’s music? Well, it is porcelain, which Haydn’s music is too, apparently! The classical basis is there, and the ornamentation, and grace, and colour and texture. Does it touch the soul as Haydn’s music often does? I leave that for you to ponder on. Responses to music and art are so varied.

Eirene is holding a torch – presumably one that doesn’t require a battery. It is possible to see this as symbolic of the Enlightenment that was blazing through Europe and beyond at that time. Haydn was very much a part of this.

Motherly imagination

“Who Is Musical?’ – not perhaps the most eye-catching title for a book, but this is indeed the title of a book by Brahms’s close friend Theodor Billroth, who Brahms dedicated his Op 51 string quartets to. Billroth was working on the text of this first ever scientific study of the nature of musicality late in his life and it was published posthumously.

A highly regarded and innovative Viennese surgeon, he was also a very good musician. I find it moving playing the viola part of the Brahms quartet knowing that he would have played this very part and that to some extent Brahms would have had his friend in mind in his musical imagination.

Billroth stated that “it is one of the superficialities of our time to see in science and art two opposites. Imagination is the mother of both.”

Max Klinger. Brahmsphantasie: Accord 1894

Brahms was a great enthusiast of the art of Max Klinger – and Klinger was equally enthusiastic about Brahms’s music. They were without doubt artistic soul mates, in touch with their subconscious and finding ways to express their imagination.

Brahms felt that writing his music was about realising what he heard in his dreams, the sphere of imagination. Perhaps with science so pivotal and revered today, and with the arts being existentially challenged, the friendship of Brahms, Klinger and Billroth can show us the importance of imagination. Against all odds, we can still dream.

My First and Last Love

Music was my first love

And it will be my last.

Music of the future

And music of the past.

To live without my music

Would be impossible to do.

In this world of troubles,

My music pulls me through.

John Miles ‘Music’

Songwriters: Breyon Jamar Prescott, Michael C. Flowers

© Universal Music Publishing Group, Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd.

I was rather keen on this song when it came out and still retain a curious fondness for it. I related to its obsessive, repeated message and found it musically and structurally interesting – well, more interesting than some. Apart from its obvious message, the lyrics also summarise the lives of many composers and artists who have produced extraordinary and elevating works of art, often in the midst of suffering and difficulty. Beethoven, Schubert, Vermeer, Van Gogh, Proust, Joyce – the list goes on and on.

The lyrics also convey something of the compulsion musicians have to make music, and touch on the reason why people act on their wish to experience live music and go as far as venturing out to attend concerts – when it is safe to do so!

Since this quartet’s live public music making was terminated, albeit temporarily, along with music making the world over as a result of lockdown, we have enjoyed putting together some videos to connect with those who have been drawn to our music making, and to show that we are still up for it. Obviously we are aware that the videos may reach an audience but it is a very different sort of chemistry from playing live, interacting with each other on the spur of the moment, and with an audience nearby very much involved in the experience and responding very personally to what the music conveys.

It means a huge amount to us as musicians that you the audience are there, and not just for financial reasons! ‘This gift (of music) will not be like the alms passed on to the beggar; it will be the sharing of a man’s every possession with his friend.’ (Hindemith) To share our music making live is an act of sharing which goes both ways. The way an audience perceives the music and the music making is incredibly important. In a way, music only properly exists and comes into being in this context.

There is no doubting, too, that music can affect us and change us deeply, and that music, like writing and the visual arts too, also has a way of shedding light on our contemporary situation, politically, socially, emotionally, even if some of the music may have been written a couple of centuries ago.

For these reasons it is a huge loss not to be able to make live music and have this communal experience of reflection and inspiration. In fact it seems to present a huge question: without the interaction of performer and audience, what is the meaning of music? It would be interesting to hear your thoughts…

Those who attended Schubert’s small chamber concerts (‘Schubertiades’) obviously had no concerns at all about social distancing:

Schubertiade. Drawing by Moritz von Schwind (www.bezirksmuseum.at)

This drawing shows how many people there actually were crowded together at these performances. (Maybe there is a little artistic license. Von Schwind was a close friend of Schubert and would have wanted to show him in the very best light.) The scene reminds me ever so slightly of the concerts that we have done in the round, where the communal experience and role of music feels particularly heightened.

‘It is a fallacy that the artist invents for himself alone. No man lives or moves or could do so, even if he wanted to, for himself alone. The actual process of artistic invention, whether it be by voice, verse, or brush, presupposes an audience.’ Vaughan Williams

A Barber bar by bar. Rossini’s Barber of Seville Overture.

Rossini’s Barber of Seville Overture cropped and styled for two.

Created in response to one of our followers who dared to suggest that Andrew might need a haircut as we sink further in to the lockdown situation.

DSQ Prokofiev + Andrew intro

Divertimento String Quartet. Prokofiev String Quartet no 2 – part of the final movement, with an introduction by Andrew Gillett.

Bridging the Silence – Clip from Adagio, string quartet no 1 in C minor by Bruch

Divertimento String Quartet playing part of the Adagio from Max Bruch’s String Quartet. Mary Eade, Lindsay Braga, Andrew Gillett and Vicky Evans