We live in a troubled world and when we are faced with such an uncertain future, it is good to have a song that lifts the spirits.

Written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, this fabulous song is as relevant today as when it was written in 1965.

Bacharach studied composition with Darius Milhaud, one of the composers in the group known as ‘Les Six’. Milhaud is the dedicatee of Erwin Schulhoff’s Five Pieces for String Quartet (1924), which is in our forthcoming concert programme. Milhaud and Schulhoff were exact contemporaries and kindred spirits in the way they incorporated jazz and traditional music into their compositions.

Erwin Schulhoff 1894 – 1942

We are excited to be including Schulhoff’s music in this programme. It is provocative, even subversive music, and the string writing is superb. Schulhoff wrote in 1919: “Music should first and foremost produce physical pleasures, yes, even ecstasies. Music is never philosophy, it arises from an ecstatic condition, finding its expression through rhythmical movement”. He was a very keen dancer, often dancing for many hours in nightclubs. He was also a brilliant pianist who had a penchant for ragtime and jazz, both of which are embedded in much of his music.

From the outset of the Five Pieces it is clear that dance is central to the work. A Viennese waltz is at play, but not as we know it in waltzes by Johann Strauss and others, but in a disjointed, somewhat grotesque way that somehow conveys the spirit and energy of the waltz and yet…..a waltz is and always has been in three time whereas Schulhoff here contrives the waltz feel within a structure of two beats in a bar, so what the listener hears is decidedly not as it looks on the page. It could be described as an inverted version of the baroque hemiola, where a piece in three beats in a bar suddenly sounds like two in a bar. Each movement of the Five Pieces is dance based – forming a suite reminiscent of the baroque suite form. After the waltz movement, there is a Serenade, then a movement infused with Czech folk music, a Tango and finally a fevered Tarantella.

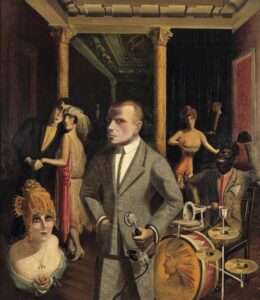

Schulhoff clearly loved dance but couldn’t resist undermining it and challenging the conventional viewpoint. His friendship with the painters Otto Dix and George Grosz, who both drew attention to the horrors of war and the prevailing fascist politics of the 1920s in Germany in an unremittingly critical way, stimulated Schulhoff’s anti-establishment nature.

Inevitably his Communist inclination became an increasing issue with the authorities; he became persona non grata, was unable to get a visa to go to America and ended up in Wülzburg prison camp in Bavaria. He died of tuberculosis there in August 1942.

Schulhoff gives the viola considerable prominence in this music. (As it happens, his sister, an artist, was called Viola.) He seems to be drawing on what could be described as the viola’s subversive tendencies – the way it can subtly transform music from within the texture of the ensemble, and its ambiguous pitch – both high and low in range. Bringing this voice to the fore is a brazen upturning of prevailing norms.

It is a privilege for us to play music that broke boundaries at a time when boundaries were clearly and harshly defined. It is a powerful reminder of the way that art can challenge – particularly relevant to us today in the context of authoritarian regimes. Schulhoff didn’t survive the particular regime of his time. Neither did the regime ultimately. His music, his voice, lives on though, still challenging, still inspiring.

Recent Comments