John Braga writes:

The string sextet is quite a rare animal. Neither Mozart nor Haydn nor Beethoven nor Schubert nor Mendelssohn ever composed one.

You wait for ages for a string sextet, then two come along at once! Divertimento String Quartet plus friends will be playing Spohr’s only sextet, written in 1848 and Brahms’s sextet no. 1 written in 1860. So, two mid-nineteenth-century works.

Brahms is of course a major composer, and very popular today. Spohr is not a well-known name to most people, so I want to start by giving some brief details of the man, his life and his legacy.

Louis Spohr was born in Brunswick, North Germany in 1784. To put this date in context, In Vienna Mozart was aged 28 and sadly had only 7 more years to live. Haydn was in full flow in Esterhazy, aged 52, and would live another 25 years. Beethoven was a lad of 14 living in Bonn.

Spohr showed early musical ability and was taken on by the Duke of Brunswick as a violin player in his orchestra at the age of 15. From that time on to the end of his long life he was able to earn a living as a player, conductor and composer. Unlike Mozart and Schubert he never had to starve in a garret. He married an 18-year-old harpist, Dorette Scheidler, in 1806 and they remained happily married until her death 28 years later. He composed 10 symphonies, several operas, 18 violin concertos, 4 clarinet concertos, many songs, 36 string quartets and a very successful octet and nonet. At the height of his fame some German critics hailed him as the natural successor to Beethoven, a claim that will seem somewhat ridiculous to us today but demonstrates how well he was regarded. He toured England on 3 occasions and was well received.

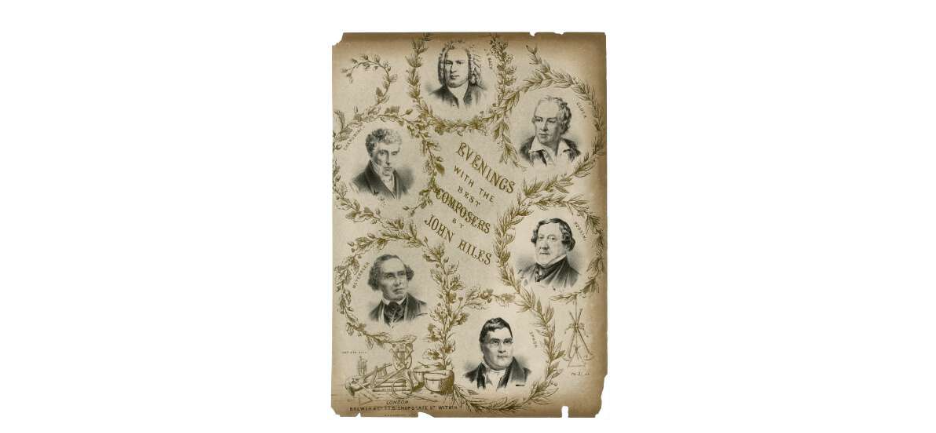

Cover sheet for ‘Evenings with the best Composers’, including amongst others, JS Bach, Gluck, Rossini and Spohr c. 1860 © The Trustees of the British Museum

He also invented the violin chin rest, the baton, and rehearsal marks for which orchestral players should be very grateful.

As a conductor he must have cut an imposing figure. He stood about 6ft 5 inches, and weighed about 18 stone

In 1808 he met Beethoven, and they worked together on Beethoven’s Ghost Trio. Spohr reported that the piano was out of tune and Beethoven’s playing harsh and careless. Later Spohr moved to Vienna and met regularly with Beethoven in coffee-houses and wine-bars. In Spohr’s biography Professor Clive Brown reports that Beethoven would regularly call in at Spohr’s apartment for tea on a Sunday afternoon when he was out for a walk. There he would play on the hearthrug with Spohr’s two young daughters – a delightful picture! It is very likely that Beethoven, who never managed to attract a wife, envied Spohr his cosy domesticity.

The sextet was written in 1848, when Spohr was 64. Not, then, a work of old age, (he died 11 years later in 1859 at the age of 75) but definitely a work of his mature years.

Audiences of the early 19th century always found Beethoven’s music a challenge to listen to. There were abrupt changes of key, strange dissonances, complex rhythms, novel orchestration. With Spohr, audiences were on more familiar ground – they felt safe. Critics, on the other hand, sometimes complained, particularly of Spohr’s later works, that his music did not progress and drew too much on earlier works. Audiences and critics frequently disagree. The conservatism that seemed a fault to critics was seen as a bonus to audiences.

Nobody knows why Spohr decided to use the sextet form for the first time at the age of 64 but he had always been keen to experiment with new formats – double quartets, a concerto for string quartet and orchestra, for example. The sextet offered him the chance to enjoy the extra sonority provided by the depth of 2 violas and 2 cellos.

1848 has come to be known for a series of revolutions that broke out throughout Europe with the aim of removing the old monarchical structures and creating independent nation-states. Spohr was a democrat and a free-thinker and welcomed this new thinking. No doubt he was inspired by the spirit of revolution as he composed the sextet. In fact, in the federation of states that would later become Germany, the revolution did not bring the hoped-for results in that year. But signs of a new order were on the wall. On the score of the sextet, Spohr wrote ‘Written in March and April, at the time of the glorious people’s revolution for the liberty, unity and greatness of Germany.’

The Dream of Worldwide Democratic and Social Republics – The Pact Between Nations, by Frédéric Sorrieu, 1848

(Note in this picture the German flag – black, red and gold – which first appeared in 1848 as a symbol of German national unity. ed.)

Despite the frisson of revolution in the air at the time, Spohr’s sextet is a beautiful, calm melodious work. Much to enjoy, nothing to shock. It is clearly the work of a composer who is not seeking to prove anything. He does not need to make a loud splash. Mendelssohn had died the year before and Spohr was widely regarded as the senior composer in Germany, a natural heir to Beethoven, rivaled only by the emerging Richard Wagner – a very different type of composer. Brahms had yet to emerge, being only 15 in 1848. Robert Schumann was sadly showing signs of the mental disorder that would kill him.

Spohr makes full use of the extra sonorities provided by the 2nd viola and 2nd cello. Many of his works contain very showy parts for the first violin (Spohr was a violin virtuoso) but here the opening theme of the first movement is played by the violas with the violins providing ornamental trills, very restrained and generally marked pianissimo. After this quiet beautiful first theme, we might expect the second theme to be a contrast, but it, too, is peaceful.

The second theme is equally melodious and serene. Nothing to frighten the horses. The whole work is remarkable for the fact that there are very few forte passages, and no fortissimo. It is also notable for a favourite device of Spohr’s, the fast descending scale decorated with trills – very difficult to play I am told!

The second movement is a tender larghetto, the third an elfin-like Scherzo and the finale is a joyous Presto.

The ‘glorious revolution’ was overthrown in Germany in 1848 and when Spohr was invited to perform in Breslau in 1849 the city was under martial law. Spohr rejected the invitation to perform, stating: “I would find myself unable to breathe, let alone to make music”. He finally made the visit in the summer of 1850 after martial law had been lifted and played the Sextet (perhaps thereby affirming his continuing belief in the principles of the revolution). A Breslau newspaper reported: “…that, at his present age [66] he plays with all the fire and energy of a young man and surmounts the greatest difficulties with amazing vigour and authority, is simply phenomenal; it has never happened before!”

Louis Spohr quartet concert. Note the double music stand.

Recent Comments