Sir Stephen Hough, pianist, writer and composer of the String Quartet (‘Les Six Rencontres’) has said: “I celebrate a certain chaos or irresolution in art.” This is quite a striking comment from such an eminent figure in the musical world! Here is one of his oil paintings:

Hough’s string quartet, an imaginary encounter with the group of French composers known as ‘Les Six’ (Auric, Durey, Honegger, Milhaud, Poulenc and Tailleferre ) is bursting with musical colour and captures the rather riotous happy-go-lucky atmosphere of Paris in the 1920s.

This string quartet was commissioned by the Takacs Quartet to partner Ravel’s String Quartet in a programme of French music that they planned. Maurice Ravel was also a member of a group of painters, composers and writers that existed between 1903 and the catastrophe of the First World War. Known as Les Apaches, the group proudly used this name when they were shouted at for expressing enthusiasm for Debussy’s opera Pelléas and Mélisande. (Debussy’s groundbreaking music was not universally approved of.) “Les Apaches” was a term of abuse; notorious underworld gangs in Paris in the late 1800s were known as Les Apaches – hooligans, basically.

Ravel’s Les Apaches was an exciting artistic melting pot of forward-looking talent. This photograph shows several members of the group at a gathering in the garden of the composer Florent Schmitt.

Some members of Les Apaches in the garden of Florent and Jeanne Schmitt circa 1910. Ravel is the man front left. In fact, Les Apaches was exclusively all-male, so this picture was taken at what was clearly a wider social gathering.

Another significant member of Les Apaches was the painter Édouard Bénédictus, who was also a chemist and designed, of all things, the prototype formula for safety glass. (They were certainly a visionary lot, those Apaches.) It is possible to see echoes of William Morris and Cézanne’s germinal cubism in the prismatic designs of Bénédictus – Cézanne was a key artistic figure for Les Apaches – and there is an affinity too with the modernist architecture of the period. This puts a different slant on the general understanding that composers such as Debussy and Ravel were writing the musical equivalent of impressionist painting.

Ravel dedicated his quartet to Gabriel Fauré, his teacher. Fauré was a hugely influential figure in the Parisian musical scene at the turn of the 19th to 20th century, a time of great upheaval politically and socially, which was reflected in the arts. Fauré was supportive of his protégé and it is clear that Ravel was greatly influenced by him, particularly in his sophisticated use of harmony and texture.

Ravel and his contemporaries were fascinated by earlier musical forms, particularly baroque dance forms. It is said that Ravel studied Haydn’s string quartets with the aim of understanding more about how to use the different colours of instruments in his compositions. It is easy to see why. Haydn achieves the most subtle gradations of colour and texture with minimal means but to maximum emotional affect. In some ways his music is almost too refined for the modern ear; we only take notice of music that slams into us and demands to be consumed. Haydn paints with the utmost clarity, subtlety and emotional sensitivity, often leading us to… nowhere, or at least to the edge of the abyss, into uncertainty. Modern purveyors of consumerism wouldn’t dare to take you to the edge because when you got there, you would find it full to the brim with their distractions, soundbites, gadgets and other debris. and you would see it for the illusion that it is. The abyss of uncertainty, possibility and creativity would be obscured by stuff.

I am reminded of walking on Dartmoor and coming across huge vistas of wilderness; brutal, elemental expanses of seemingly featureless moorland. In a moment I might be subsumed by it, becoming one with it – along with those unfortunate young soldiers who over the years must surely have lost their way in it during their training, never to be seen again.

I think that is where Haydn takes us, but with his friendly hand to hold ours – and therein lies a paradox. He is not afraid to enter the wilderness, and we all have our experience of bleakness, but so often there is wit and fun along the way. Haydn’s music is immensely rewarding to play, for those reasons. I hope that you feel persuaded to come along and experience all the different musical colours of this programme with us.

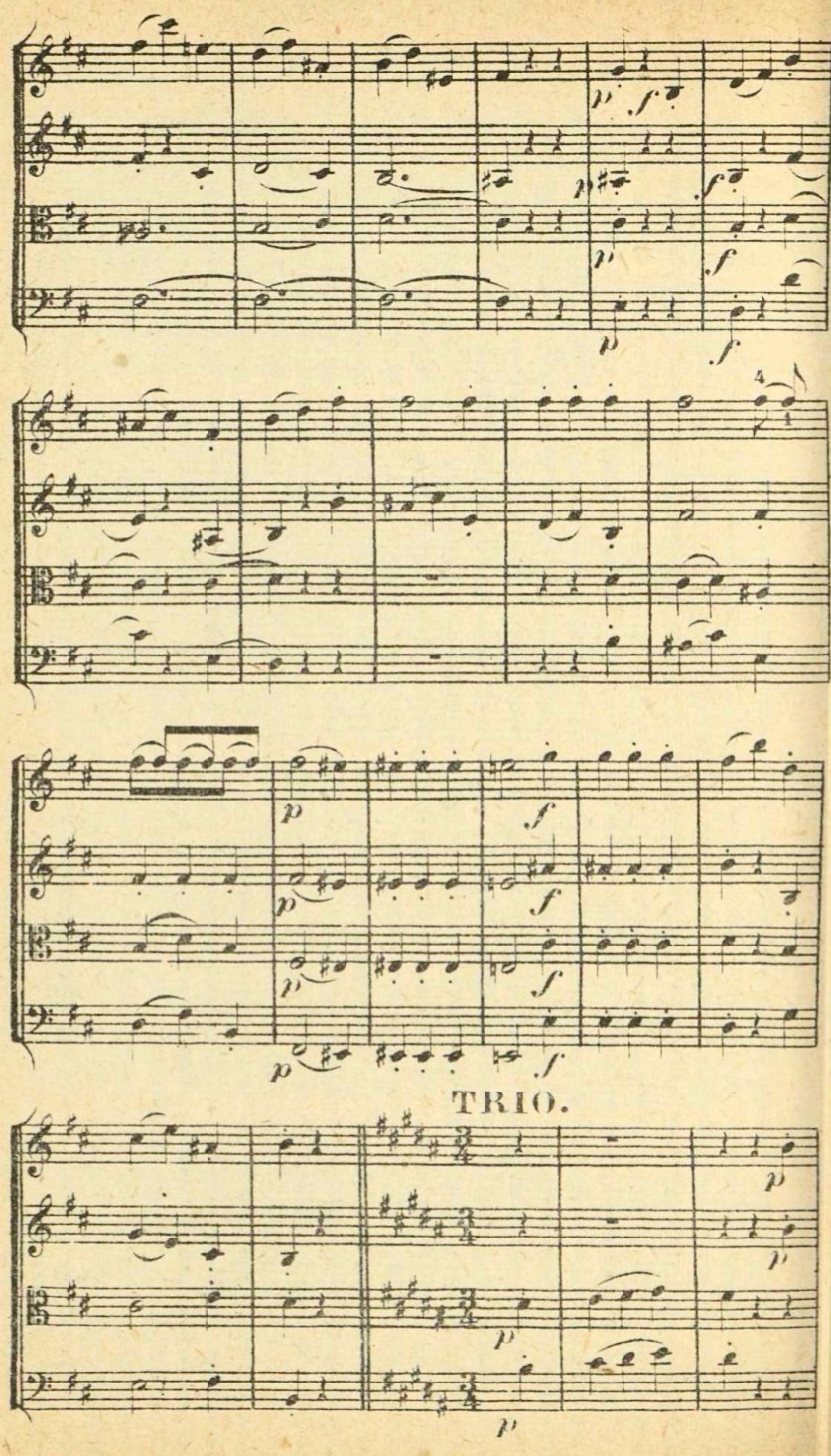

As a postscript and teaser, below is an excerpt from Haydn’s Scherzo and Trio from op 33 no 1. His scores always look very clean, ordered and relatively simple but what is actually going on in the music is eventful, to say the least – and too numerous to go into here without critics recommending that the author is given a good hiding. Suffice to say that what Haydn does here is pretty cheeky, and funny for the musicians – in the Trio section he basically provides music that is an opportunity for B major scale practice, in a work that is primarily in B minor!

Recent Comments