DSQ blog

What’s the score?

Franz Schubert’s autograph manuscript of the song ‘An Rosa’ composed 1815, a year before his string quartet in E, D 353

“What a diary is to others, in which their momentary emotions and so forth are recorded, so to Schubert was music paper, to which he entrusted all his moods. His thoroughly musical soul wrote notes where others used words.” So wrote Schumann.

Scribbles on paper that translate to expressive musical utterances when performed are the basic means of transport for the realisation of composers’ ideas. They are really interesting for performers to see (as long as they are available to see – many are not, or they have disappeared over the years) and often provide helpful information on the genesis of a musical work.

Brahms used his manuscripts as working documents, editing and re-editing his compositions, often over many years, which was the case with the op 51 string quartets, as it was with his 1st symphony, finished when he was forty-three after many years of careful refining.

Later in life, Brahms said: “Neither Schumann, Wagner nor I were properly schooled. Talent was the decisive factor. Each of us had to find his own way. Schumann took one way, Wagner another, and I a third. But none of us really learnt what is right.” This is an astonishing statement even if it is primarily to do with an idealistic aim to live up to the contrapuntal disciplines that were so superbly manifested in previous ages by such people as JS Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.

Although the first public performance of op 51 (1873) was given by Brahms’s close friend, the celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim and his quartet, the music had undergone careful assessment and adjustment with the help of the Florentine Quartet who played the music to Brahms in private. The composer and performer relationship in the developing of ideas in western classical music was and remains indivisible.

There is one very indistinct sound recording of Brahms playing the piano but as yet there has been no discernible residue detected in the atmosphere of the musical vibrations resulting from Schubert’s peregrinations along the keyboard of his piano all those years ago. Maybe science will achieve this one day; one can live in hope that this will be achieved and we will be able to hear performances by Bach, Mozart, Paganini and others too.

Astor Piazzolla’s superb bandoneon playing has been well captured in numerous sound recordings. In a way, the manuscript score of the past has been taken over by recording as our way into the mind of the composer. This is a very topical subject which we will be considering in more depth in a future blog.

David Harrington of the Kronos Quartet who worked with Piazzolla has said: “When audiences and performers that hadn’t encountered Piazzolla before heard his music, they heard something new… an intensity that we’ve read about, but hadn’t experienced, when you grow up hearing about Beethoven and intensity. You can listen to Barton or the music of Thelonius Monk or John Coltrane or Jimi Hendrix and read about their intensity in books. These are people that tap into the fact that music is the root, a central part of the human experience. Some musicians reach a place that is inexplicable, but when you hear it, you recognise it. When you encounter Piazzolla, you realise he is part of that same conversation.”

And the Argentinian musicologist Maria Susana Azzi puts it very aptly and in a way that encompasses all three composers of our current programme: “Tango (and equally this could be the manuscript score of the earlier composers – ed.) is more than just notes…(with its) rhythm that is at once love and dream, pain and reality (and) its special qualities of freedom, passion and ecstasy… it is dance, poetry, song and gestures, ethos and a philosophy of life.”

A splash of colour

Sir Stephen Hough, pianist, writer and composer of the String Quartet (‘Les Six Rencontres’) has said: “I celebrate a certain chaos or irresolution in art.” This is quite a striking comment from such an eminent figure in the musical world! Here is one of his oil paintings:

Hough’s string quartet, an imaginary encounter with the group of French composers known as ‘Les Six’ (Auric, Durey, Honegger, Milhaud, Poulenc and Tailleferre ) is bursting with musical colour and captures the rather riotous happy-go-lucky atmosphere of Paris in the 1920s.

This string quartet was commissioned by the Takacs Quartet to partner Ravel’s String Quartet in a programme of French music that they planned. Maurice Ravel was also a member of a group of painters, composers and writers that existed between 1903 and the catastrophe of the First World War. Known as Les Apaches, the group proudly used this name when they were shouted at for expressing enthusiasm for Debussy’s opera Pelléas and Mélisande. (Debussy’s groundbreaking music was not universally approved of.) “Les Apaches” was a term of abuse; notorious underworld gangs in Paris in the late 1800s were known as Les Apaches – hooligans, basically.

Ravel’s Les Apaches was an exciting artistic melting pot of forward-looking talent. This photograph shows several members of the group at a gathering in the garden of the composer Florent Schmitt.

Some members of Les Apaches in the garden of Florent and Jeanne Schmitt circa 1910. Ravel is the man front left. In fact, Les Apaches was exclusively all-male, so this picture was taken at what was clearly a wider social gathering.

Another significant member of Les Apaches was the painter Édouard Bénédictus, who was also a chemist and designed, of all things, the prototype formula for safety glass. (They were certainly a visionary lot, those Apaches.) It is possible to see echoes of William Morris and Cézanne’s germinal cubism in the prismatic designs of Bénédictus – Cézanne was a key artistic figure for Les Apaches – and there is an affinity too with the modernist architecture of the period. This puts a different slant on the general understanding that composers such as Debussy and Ravel were writing the musical equivalent of impressionist painting.

Ravel dedicated his quartet to Gabriel Fauré, his teacher. Fauré was a hugely influential figure in the Parisian musical scene at the turn of the 19th to 20th century, a time of great upheaval politically and socially, which was reflected in the arts. Fauré was supportive of his protégé and it is clear that Ravel was greatly influenced by him, particularly in his sophisticated use of harmony and texture.

Ravel and his contemporaries were fascinated by earlier musical forms, particularly baroque dance forms. It is said that Ravel studied Haydn’s string quartets with the aim of understanding more about how to use the different colours of instruments in his compositions. It is easy to see why. Haydn achieves the most subtle gradations of colour and texture with minimal means but to maximum emotional affect. In some ways his music is almost too refined for the modern ear; we only take notice of music that slams into us and demands to be consumed. Haydn paints with the utmost clarity, subtlety and emotional sensitivity, often leading us to… nowhere, or at least to the edge of the abyss, into uncertainty. Modern purveyors of consumerism wouldn’t dare to take you to the edge because when you got there, you would find it full to the brim with their distractions, soundbites, gadgets and other debris. and you would see it for the illusion that it is. The abyss of uncertainty, possibility and creativity would be obscured by stuff.

I am reminded of walking on Dartmoor and coming across huge vistas of wilderness; brutal, elemental expanses of seemingly featureless moorland. In a moment I might be subsumed by it, becoming one with it – along with those unfortunate young soldiers who over the years must surely have lost their way in it during their training, never to be seen again.

I think that is where Haydn takes us, but with his friendly hand to hold ours – and therein lies a paradox. He is not afraid to enter the wilderness, and we all have our experience of bleakness, but so often there is wit and fun along the way. Haydn’s music is immensely rewarding to play, for those reasons. I hope that you feel persuaded to come along and experience all the different musical colours of this programme with us.

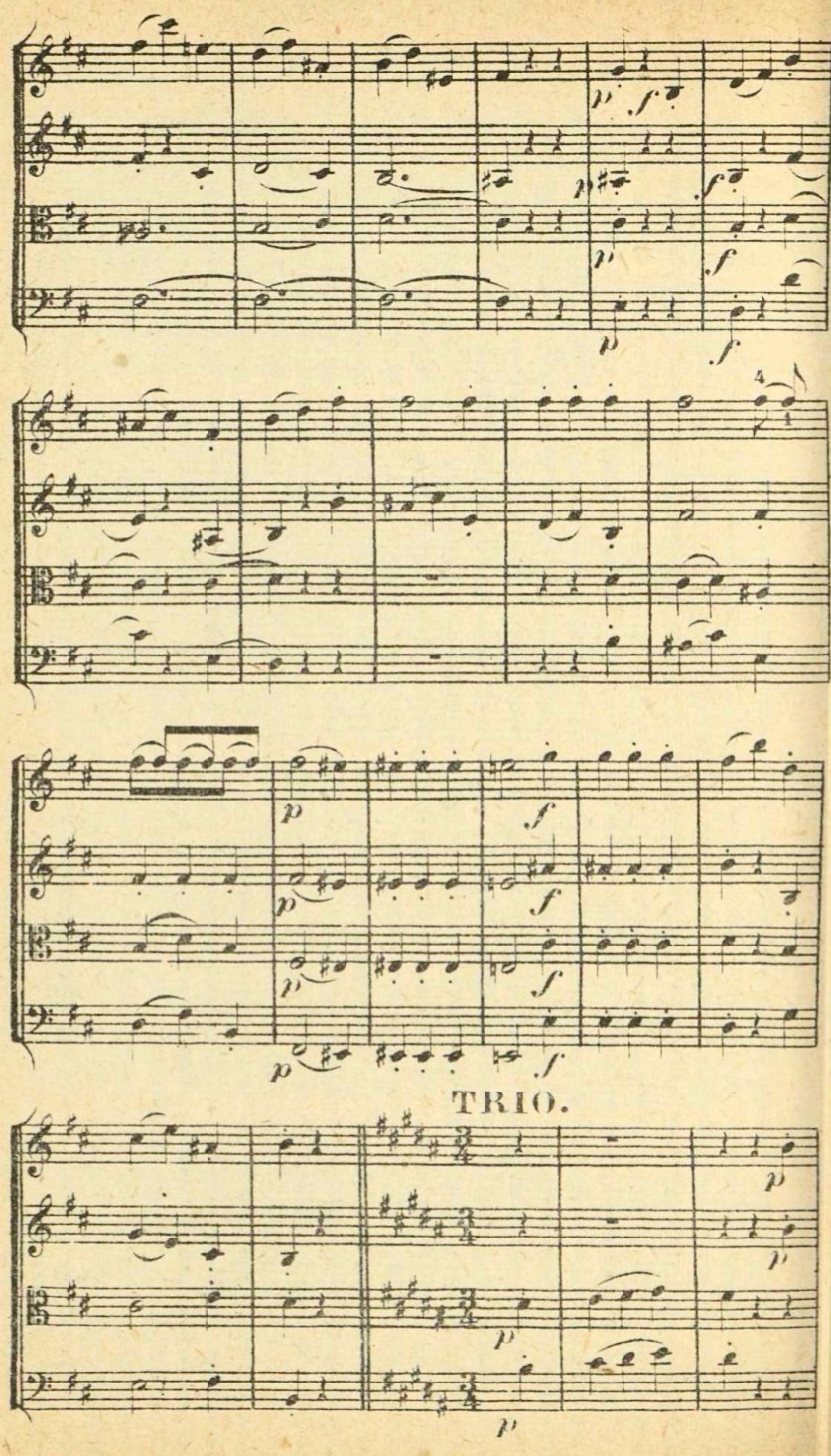

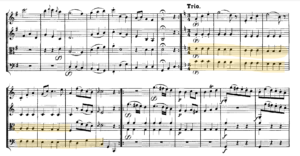

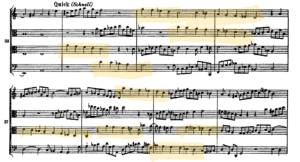

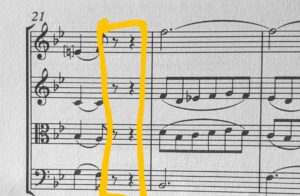

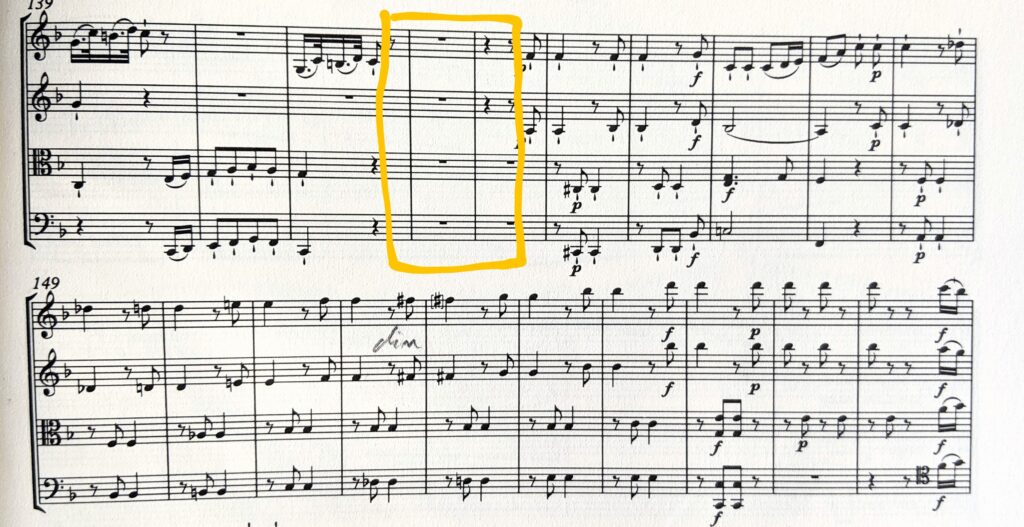

As a postscript and teaser, below is an excerpt from Haydn’s Scherzo and Trio from op 33 no 1. His scores always look very clean, ordered and relatively simple but what is actually going on in the music is eventful, to say the least – and too numerous to go into here without critics recommending that the author is given a good hiding. Suffice to say that what Haydn does here is pretty cheeky, and funny for the musicians – in the Trio section he basically provides music that is an opportunity for B major scale practice, in a work that is primarily in B minor!

The cause of a smile

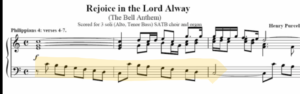

The beginning of Yesterday Once More by The Carpenters. What could possibly link this timeless 1970s song to Purcell’s timeless anthem Rejoice in the Lord alway, written almost three hundred years earlier?

When we focus on the downward travelling bass line in both, it soon becomes apparent.

Carpenters:

Purcell:

– music written hundreds of miles and years apart but sharing the common musical device of the descending motif, giving the music a sense of direction and harmonic progression. (The Carpenters’ For All We Know is very similar at the beginning.) In a DSQ programme that contains three works by English composers and one by Mozart, it is clear that there are many connections. Within the music there is evidence of the universality of origins and influences.

There are several more descending lines integral to the works that we are playing.

1.Britten

2. Mozart

Sometimes these descending lines give a strong sense of where the bass line is heading. At other times, it isn’t so obvious. In the beginning of the Elgar quartet, the cello (bass) line wanders down while the first violin heads upwards, in a way not dissimilar to the Mozart example above.

3. Elgar (beginning)

Later in the first movement the downward line is more thematic:

4. Purcell

Purcell’s downward lines roll out in profusion.

In some ways, Purcell’s music sounds more modern than any of the other more recent composers featured in our programme. Elgar definitely wanders off into new territory, for him at least. There are echoes of Wagner and Debussy but somehow it is quintessentially Elgar. It feels appropriate to play Elgar immediately after Purcell – they are surely questing, kindred spirits spanning the centuries.

In the videos I describe some of the descending lines as like a tolling bell. Purcell’s anthem, Rejoice in the Lord alway is also called the ‘Bell anthem’ because of the downward bell-like movement of the bass line – so much more than a bass line! I studied this anthem in my early teens and it really affected me way back then. The Carpenters also had their place in my listening of that time. I wasn’t aware of the link between the two but perhaps it takes time to become aware of the universality of things.

When I was young I’d listen to the radio

Waitin’ for my fav’rite songs

When they played I’d sing along

It made me smile

(Richard Lynn Carpenter and John Bettis)

Time for the opera interval

Oh to have heard Teresa Stolz sing!

Giuseppe Verdi, in his sixtieth year, was in Naples assisting in the production of his latest opera, Aida, when the lead soprano, Teresa Stolz became ill and everything was put on hold. Stolz (forty-one at the time) was his soprano of choice. (She performed the soprano solo in the first performance of his Requiem the following year – 1874.) His wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, had been a celebrated soprano too, but had retired. His first wife, Margherita Barezzi, had also been a singer.

Surely the voices of the women that he knew and his relationships with them fed his musical imagination. The same could be said of Mozart, for sure, and many other composers. It is as if there is something of these women (and men of course) embedded, almost recorded, in the music. Could this be, in a way, a hugely respectful and fond way of appreciating and celebrating them that lasts forever? A debatable subject, for sure, especially bearing in mind their varying roles and reputations in the drama, but something worth debating, perhaps.

Holed up in his hotel, the Grande Albergo delle Crocelle (favourite haunt of, amongst others, Casanova some time back), a beautiful spot by the sea, fifteen minutes walk from the theatre, Verdi must have been aware that there were some string players in the theatre orchestra with time on their hands and he proceeded to pen a large scale work for string quartet which had its first performance in the hotel. He was modest about its qualities but it is in reality an astonishingly assured and brilliant work, infused with operatic drama and ‘singing’ melodies.

Verdi was very involved in modernising opera theatre orchestras, or at least attempting to persuade theatre managers to change things. Opera orchestras had become, basically, large wind bands, and he pushed for more strings, particularly lower strings, to achieve a richer string sound that balanced with the wind instruments better. He (along with other forward thinking composers and academics) also insisted on changes in the layout of the orchestra because many opera houses had become stuck in eighteenth century layouts that didn’t reflect what was happening in operatic writing as it developed through the nineteenth century. He also requested a standard pitch of A = 435, which is a little lower than what is considered standard pitch today. His string quartet is an indicator of the standard of string writing and playing that he was trying to achieve. It is superb – and demanding – string writing, so clearly straight out of the opera.

Teresa was to remain a part of Giuseppe’s life to the end. After his wife died, Teresa went to live with him until his death. The exact nature of their relationship is not known. The story of their lives and loves could very easily be turned into an opera.

We are also playing a short piece for strings – Crisantemi – by Giacomo Puccini. Primarily an operatic composer, and one of the greatest composers ever working in that genre, he was moved to write this elegiac piece in a single night in January 1890, on hearing that his forty-four year old friend, the Duke of Aosta, had died of pneumonia.

Prince Amedeo had fought in the Third Italian War of Independence and was something of a national hero, having been wounded in the Battle of Custoza.

Clearly intended to show off his considerable assets, this portrait may have contributed, in an extraordinary turn of events, to him being chosen to be King of Spain from 1870 – 1873.

Having been installed as king, it turned out that the level of political turmoil in Spain at the time made his position unworkable and he decided to leave and head back to Italy. Still seen as a hero in Italy, his return was greatly celebrated. After his wife’s death, his second marriage was frowned upon by many, but his death, especially at a relatively young age, was a cause for national mourning. Puccini’s Crisantemi is tragic, tender and heartfelt, devoid of pomp or bombast. (It is believed that Madame Chrysanthème, a novel – published 1887 – by Pierre Lotti, about a young French naval officer who enters into a temporary marriage with a geisha while stationed in Japan, was partly the inspiration for Puccini’s Opera Madama Butterfly. The connection between Madame Chrysanthème and Crisantemi is potentially a very interesting subject, so far strangely unexplored and it is likely that it will remain that way unless a particularly inquisitive student reads this blog post and thinks that such a study would make a good subject for a degree.)

Amedeo’s life, and indeed the lives of those close to him, would also potentially make for for good operatic – or film material. We are available, as a quartet, to be part of the production – period costumes and all – and we would be happy to negotiate a fee for our services proportionate to the predictable huge success of the venture.

Rota’s eternal dilemma

The music of Nino Rota (b. 1911 d. 1979) may not be a familiar name to concert audiences but such iconic films as The Godfather and La Dolce Vita will surely be well known to many. Rota wrote the soundtrack for these Federico Fellini directed films, as well as many other films such as Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. He is a hugely significant figure in the history of film making. In particular, he helped Italian film develop its unique character. Fellini called him his ‘most precious collaborator. He had a geometric imagination, a musical approach worthy of celestial spheres. He thus had no need to see images from my movies. I clearly realised he was not concerned with images at all. His world was inner, inside himself, and reality had no way to enter it.’

Rota was a prolific composer in other musical forms too – ballet, opera, concertos and chamber music. His Quartetto per archi (Quartet for strings) was written just after the Second World War, in the same period that he was writing his first film scores. There is definitely something rather atmospheric and filmic about this section in the last movement:

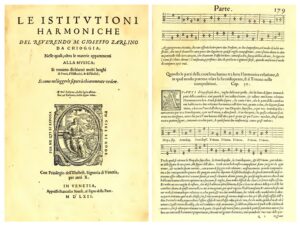

Perhaps it is possible to hear a reference to ceremonial courtly early music in the louder, livelier section here. As a student Rota had written a thesis on the Venetian Renaissance composer and music theorist, Gioseffo Zarlino.

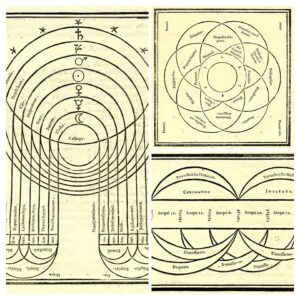

There is something of the celestial spheres suggested in the illustrations of Zarlino’s groundbreaking treatise, Le Institutioni Harmoniche, which must have appealed to Rota. (Zarlino was an exact Venetian contemporary of the painter Tintoretto, whose St Ursula painting is mentioned in the previous blog post here. Surely they must have known each other.)

Whilst Rota was at the forefront of the new wave of post war culture, his fascination with the golden age of Italian music inevitably found its way into his compositional style, as can be heard in this transition in the slow movement:

“When I’m creating at the piano, I tend to feel happy” said Rota – “but the eternal dilemma – how can we be happy amid the unhappiness of others? I’d do everything I could to give everyone a moment of happiness. That’s what’s at the heart of my music.” Tantamount to an artistic manifesto, this says much about him as a person and there is no doubt that he was successful in achieving what he set out to do.

From Mendicanti to cognoscenti

The Rio dei Mendicanti (Ospedale on the right) by Francesco Guardi c. 1780-90, courtesy York Museums and Gallery Trust

Our Italian programme begins with the music of a courageous and determined eighteenth century woman. Maddalena Lombardini’s impoverished parents took her to audition for a place at the Ospedale di San Lazzaro dei Mendicanti, one of Venice’s charitable institutions for the poor, sick and orphaned, which also served as educational establishments. In particular, musical skills were nurtured, presumably with the expectation of the pupils’ involvement in the music in the chapel there. She was accepted.

Lombardini was clearly a talented young musician and managed to get permission to have violin lessons with Tartini, violinist and musical theorist, who lived in Padua. She studied composition with Ferdinando Bertoni, choirmaster at the Ospedale.

Her sights were soon set beyond the walls of the Ospedale. In order to be released from its confines she needed a dowry. She married another violinist composer, Lodovico Sirmen, and they left to tour Europe.

They performed to acclaim in Turin, Paris and London, often playing their own compositions – concertos, duets, and no doubt quartets. A set of six quartets (we are playing No 6) published in Paris in 1769 was considered to have been co-written by the couple but more recently the authorship has been more clearly identified as being that of Maddalena herself. On the cusp of the early classical style that was being developed by Haydn, and contemporary with his earliest string quartets, there is still a flavour in her music of the courtly airs and graces that she would have encountered on her visits to the cultural capitals of Europe.

Despite the early flowering of her talent and fame, she ultimately got rather left behind. Her violin playing became to be seen as old fashioned. She turned to singing as a career, even performing as far away as St Petersburg but this new musical direction didn’t really work out and she subsequently returned to Venice with her travelling companion, Giuseppe Terzi, a priest – this arrangement was evidently not uncommon at the time. (Her husband Lodovico had long since left her, taking their daughter Alessandra to Ravenna, where he had employment and became associated with Countess Zerletti.) In 1795 Maddalena and Giuseppe jointly adopted a child. The couple must have been close, to say the least. One wonders what Maddalena’s inner life was, balancing her musical aspirations, cosmopolitan experiences and maternal feelings.

It is very likely that the young Maddalena gazed at Tintoretto’s painting, St Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins, which was installed in the chapel at the Ospedale. It is a very dramatic picture, depicting a scene from the life of the patron saint of schoolgirls, St Ursula, that could almost be the inspiration for a film scene. In particular, the eye is drawn to the huge ships in the background and of course that extraordinary weightless figure flying through the air. There is so much movement in it, so much travelling.

I think it would be a stretch of the imagination to interpret this painting as in any way feminist but perhaps there is an energy in it that is reflected in the impetus of Maddalena’s desire to break out of the Ospedale, travel far and wide and express her feelings through her music.

The gift of silence

Some years ago a scientific research group put out a request for antique objects, ornaments, artefacts, containing air that had been sealed in when they were made. The idea was that this air could be analysed for levels of pollution that existed in Victorian times, or whenever the object was made, in comparison with modern levels.

The sealed air makes me think of the silences in Haydn’s music. Surrounded and sealed by the notes around them, Haydn’s silences are pockets of silence from the 18th century. We are connected to the silence that he experienced and that listeners have experienced and will experience whenever the piece is played. It is also, for some, a communal experience of awareness of a greater universal silence, in the listening present moment of a performance. (In a way, the silence gives us a more authentic experience of the 18th century than the actual notes, because the sounds that we hear are the result of interpretation and such things as the sounds of the instruments and styles of playing, which have changed – but silence hasn’t.)

Haydn leads us to the silence, enabling it to grace our lives for a moment. Perhaps this is his greatest gift to us.

There is another striking silence in this quartet – if silence can be striking.

This one is particularly clever. It catches the players off guard – a deliberate banana skin moment when the music evaporates unexpectedly. Where has the music gone?! How are we going to get it back again? Silence rules. Everything comes out of silence and goes back into silence..

What follows this particular moment of silence is a passage of astonishing harmonic invention. It passes by quite quickly so here it is, slower.

Wagner – yes, Wagner!! – comes to mind. I would never have imagined it in Haydn. It just goes to show how original and modern Haydn was in his writing. With minimal means, Haydn breaks the bounds of the formal constraints of classical structures.

The more we play some pieces of music, the more they reveal themselves to us – and often the more mysterious they become. Could this be a definition of great music? It is certainly the way of Haydn quartets which, with seemingly simple resources, give us so much to ponder and enjoy.

Enigmas and dreams

It is always good to come across composers who we have never heard of before but whose music comes to life with vivid immediacy when the bow strokes the string. One such composer is Ignacy Dobrzyński (born in what was then Polish-Ukraine), a fellow classmate of Frédéric Chopin at the Warsaw Conservatoire.

Dobrzyński and Chopin were encouraged by their teacher Józef Elsner to incorporate polonaises, mazurkas and other traditional Polish folk music into their compositions. Their paths were ultimately very different. Chopin was at the forefront of the Romantic movement, his star ever rising. Dobrzyński, famous in his time, became rather lost in the foggy hinterland of less well known composers but his music deserves to be heard. We are pleased to be bringing his quartet in E minor op 7 to life.

Dobrzyński doesn’t step far out of the magnetic field of Joseph Haydn’s influence in his quartet.

Haydn’s op 50 no 5 is not one of his better known quartets but it is as supreme an example of quartet writing as any – succinct, unpredictable, fascinating. The dream-like slow movement holds its magical spell throughout its relatively brief appearance – a reverie in sound. What is the reverie about? Who knows?! This is surely one of the key elements of the very best art – that it offers our imagination opportunities to roam and dream without boundaries or foregone conclusions.

Shostakovich’s music stimulates the imagination too. What is the link between the 7th string quartet dedication – to his recently deceased wife – and the music within this work? (He was by all accounts deeply distressed by her death.)

Nina and Dmitri Shostakovich 1943 Photographed by A. Less © 2001 Cultural Heritage Series/Artistic Director Oksana Dvornichenko

As with so much of his music, we are left guessing to a large extent, and we are left with enigmas. One enigma in this work is announced very clearly and meaningfully by the viola near the beginning of the 3rd movement. After the violins and cello have launched into a cascade of violent semiquavers (described by some as a dog barking), the viola plays four quiet notes. They clearly mean something. But what? The notes can be analysed as forming a theme or part of a code but their presence in the context of the movement seems extremely telling, and yet we will never know for sure what the inner meaning is. We are simply drawn into a place where, in witnessing the enigma, we validate its potential to stimulate the imagination.

I feel a strong influence of the faster, turbulent section of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet in this third movement. It is unbridled energy, fearless, fearsome. Perhaps the ending of the work wouldn’t be so effective without this sword-fight of a movement, which normally results in a few lost hairs in all respects. See you at the next series, when we’ll be wearing some pretty fetching wigs, no doubt.

The emancipation of the cello

It was difficult to keep a tab on Boccherini. At closing time he would already have travelled to another country, avidly seeking his next musical employment.

Born in Lucca, Italy, in 1743, he started playing the cello aged five, initially taught by his father. He was sent to study in Rome when he was thirteen. Father and son travelled to Vienna in 1757 to play in the Burgtheater orchestra. He subsequently moved to Spain, in the employment of royalty, where his career really took off.

Fashion has certainly changed since Boccherini’s time. What a fantastic outfit he is wearing! This painting records very accurately, too, the bow and cello of the period and the method of playing it – the bow hold, left hand position and the way the cello is supported by the legs rather than with the aid of a spike in the base of the cello resting on the floor, as is the way with modern cello playing.

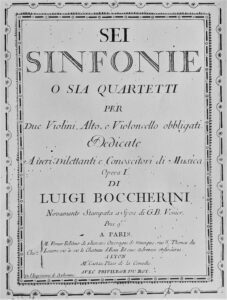

Op 2 No 1, in our current concert series, is believed to be Boccherini’s first published quartet (1761), and as such it is probably one of the first string quartets ever written, contemporaneous with Haydn’s first quartet works.

This title page is a veritable treasure trove of information. The meaning of symphonie/symphony has changed since Boccherini’s time. He used it in the sense of people playing together rather than the subsequent transition of the meaning to imply something more large scale and orchestral. Then he says ‘O sia quartetti’. This suggests a massive shift into new territory – where the four instruments together were the new symphony – the new togetherness, which he invited people to enter into, with his dedication ‘to true amateurs and connoisseurs of music’. This was music for everybody to enjoy, in their homes, in a way that was conversational and intimate. There was one caveat not mentioned, though. You had to have a very good cellist in your quartet…

Boccherini was the cello virtuoso of his age and even in the earlier works the cello is given way more to do than was considered proper up to that time. It could be described as an emancipation. As a result cellists both love and dread his music. However, whatever feats of musical gymnastics the cellist is required to do, somehow this music generally maintains an air of gracefulness and tender expression – so characteristic of Boccherini.

The benefits of diplomacy

Palace and Garden of Prince Razumovsky in the Viennese Suburb of Landstrasse (c. 1825). Watercolour by Eduard Gurk (1801–41). Wien Museum. Photo: Imagno / Getty Images

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827), so fond of walks in woods and in the countryside, must have been in his element in the extensive gardens of his patron Count Andrey Razumovsky (1752 – 1836), the Russian ambassador in Vienna. Extensive is an understatement. The Count’s residence and gardens were conceived on a grand scale to impress. The mannered, ‘artificial’ style of French gardens that had been popular was given short shrift. English garden design was chosen instead, showcasing nature through irregular, secluded paths and viewpoints onto magnificent natural vistas. One can easily imagine Beethoven’s 6th (‘Pastoral’) symphony – dedicated to Count Razumovsky – as the soundtrack to a tour around the gardens.

Razumovsky was an art collector and played the violin. He also played the torban, a Ukrainian traditional instrument – with good reason; he was born into Ukrainian aristocracy and clearly valued his Ukrainian heritage.

Without doubt, his artistic interests were bound up with his diplomatic role. Conveying an impression of an acute awareness of pan-European culture was part of his diplomatic mission.

His enthusiasm for music extended to employing an excellent string quartet led by Ignaz Shuppanzigh – a good friend of Beethoven – as part of his numerous employees. Razumovsky even provided them with pensions on their retirement.

The Schuppanzigh Quartet holds an important place in the history of chamber music. These were the first musicians in Europe whose careers existed around chamber music rather than orchestral or solo playing. They also premiered many important new works, including the three Op 59 quartets that Razumovsky commissioned Beethoven to write.

All of Beethoven’s ‘Razumovsky’ quartets include Russian themes, although it is unclear whether this was a request by the Count to include them or whether Beethoven included them out of respect and gratitude. The slow movement of Op 59 No 3, which we are playing in our current programme, contains the most Russian sounding music in this quartet – possibly suggesting the vast expanses of the steppes rather than the luxury of sumptuous palaces.

Part of Razumovsky’s palace burnt down in the early hours of New Year’s Day 1815, the evening after a ball at which the guest of honour had been Tsar Alexander 1. A large amount of Razumovsky’s art collection went up in flames. Distraught, he became a shadow of his former self, living in seclusion in Vienna until his death in 1836.

Wealth and influence might fade away but Beethoven’s music speaks to each new generation with startling urgency.