DSQ blog

More Spohr

Rehearsing the first movement of the Spohr sextet. Gentle, warm music that perhaps doesn’t have the depth of Brahms but its texture bears a striking similarity in parts to the music of Richard Strauss – the lyricism, the shifts of key, the fluttering trills.

There is a lot of trilling to do in Spohr. They are a characteristic part of his music, for sure. He was a well known and influential violin teacher and articulating trills was a skill that was very much a part of his method. What is particularly challenging for the performer is the way he incorporates trills in runs of fast notes that are already tricky enough without having to add extra twiddles! But we enjoy it all the same, keeping our fingers nimble and ready for action.

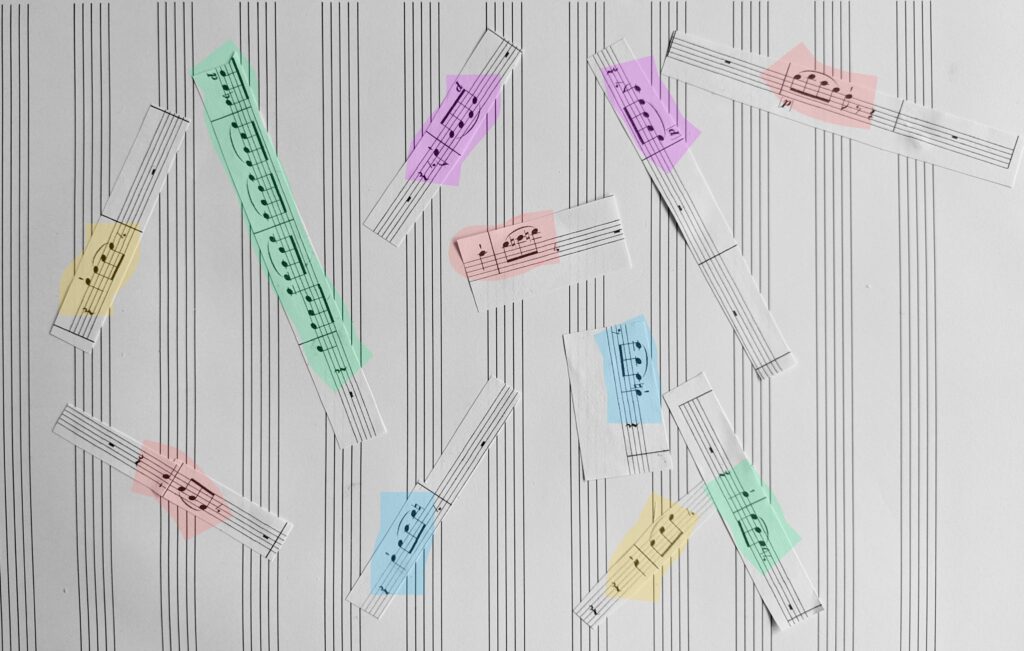

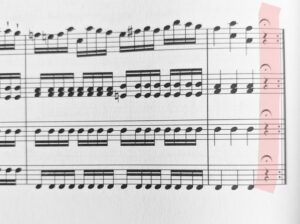

Here is an example of the trilling going on between first violin and viola in that same movement:

And from the slow movement, less trilling, more collective enjoyment in the melodic sweep and contrasting rhythmic decisiveness.

As mentioned in a previous blog post, one of Spohr’s innovations was in providing rehearsal letters in the music to make it easier for musicians to rehearse the music together, so that they could go beyond such practicalities and engage with more profound issues such as phrasing and interpretation. I wonder what Spohr would have made of the deep philosophical discussion going on here: (you may need to turn up your volume to hear our voices.)

Music of the heart

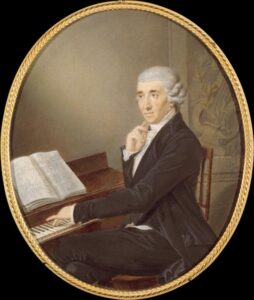

Compared to many artists and musicians – Berlioz for example, or Mozart, or van Gogh – we know very little about the inner life of Johannes Brahms. He took great pains to dispose of any trail that would give anything away, even requesting of friends that they destroy evidence of correspondence from him. What we are left with is his music, which is surely as confessional as any words written in a letter, and tells us so much about him. Surely he was complicit in this manner of self-revelation.

“If there is anyone here I have not offended, I apologise”, he said when leaving a party. Amusing as it is, it shows how single minded he was. (That such irascibility may have been the result of sleep apnoea is by the by.)

By the time that Brahms composed his Op 18 string sextet in 1860, aged 37, he had written a large amount of music, including, it is believed, twenty string quartets. Most of this he had destroyed in a determined striving for what he thought was worthwhile, particularly in relation to the iconic musical forbears he so revered.

So this sextet was written, surprisingly, before his first official string quartet, Op 51 No 1. He needed time to find a way to form his own statement and response to the acknowledged supreme writers of quartet music – Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Although he learnt the violin when he was young, his primary instrument was the piano, and he was a piano teacher in the early part of his career. One of his pupils, Minna Völckers, recalled:

‘Between Friday and Tuesday I had to learn a study by Cramer, a prelude from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and the first movement of a sonata by Beethoven. That seemed to me to be an insurmountable task but it went better than I had imagined. I had to play him scales every time. He was very exact with everything and placed special emphasis on a loose wrist. Brahms could not be bettered as a teacher. He was gentle and kind, without praising much. I quickly made big strides with him. I really wanted to play some of his compositions, but hesitated to say so to him. My mother did it for me. “Yes”, he said, “the things are still too difficult, but I will play duets with her” and we had to work on his sextet Op 18, which we immediately got down to in the next lesson. I had to play primo, and we went through it very exactly, and my family were also delighted by the fine music. None of us could ever understand the stupid twaddle that one so often heard about him, that his music was confused. Sometimes, if I asked him, he played fugues after the lesson.’

Presumably the version of the sextet mentioned here would have been a piano duet version; this was common at this time, to make such works available for people to play in their homes if they had a piano, which was very likely.

Brahms gained a huge amount of understanding about string playing from two very significant violinists in his life; Joseph Joachim, considered to be the greatest violinist at the time and a lifelong personal friend of Brahms, and Ede Remenyi, who Brahms toured with giving recitals in 1853. Remenyi had Roma music in his blood and Brahms soon started to incorporate elements of this traditional music in his compositions.

The scherzo of the sextet op 18 has an exuberant energy to it that surely stems from this source of inspiration:

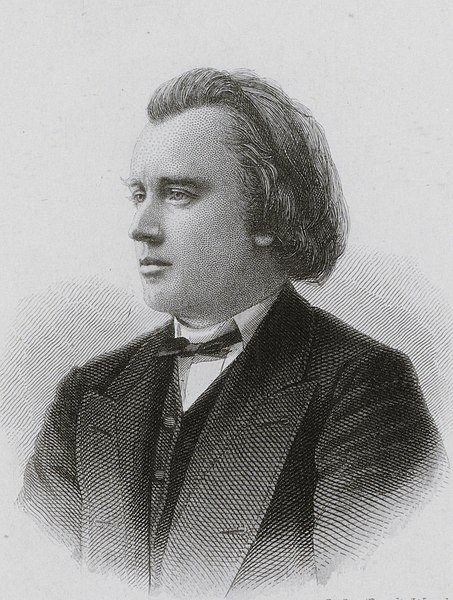

We are probably most familiar with photographs of the older, bearded Brahms. The younger version, as in the two portraits above, makes quite a different impression. It seems that, despite our impression of a very handsome young man, he was not a man brimming with self confidence. It is possible that his decision to break off his engagement to Agathe von Siebold was brought on by the unfavourable audience response to his first piano concerto and he felt that he would be an inadequate partner for her. He was also very close to Clara Schumann but this relationship did not become a permanent commitment.

Is there something fatalistic, or even funereal in this passage in the slow movement of the sextet, expressing resignation at his state of being?:

This excerpt shows well Brahms’s affinity with the richer darker tones of the musical spectrum that he found able to achieve with the help of the extra viola and cello in the sextet. The pizzicati of the violins provide a lovely touch, lightening the atmosphere a little. He knew just how to express his inner feelings in musical form.

Four plus two = Spohr

John Braga writes:

The string sextet is quite a rare animal. Neither Mozart nor Haydn nor Beethoven nor Schubert nor Mendelssohn ever composed one.

You wait for ages for a string sextet, then two come along at once! Divertimento String Quartet plus friends will be playing Spohr’s only sextet, written in 1848 and Brahms’s sextet no. 1 written in 1860. So, two mid-nineteenth-century works.

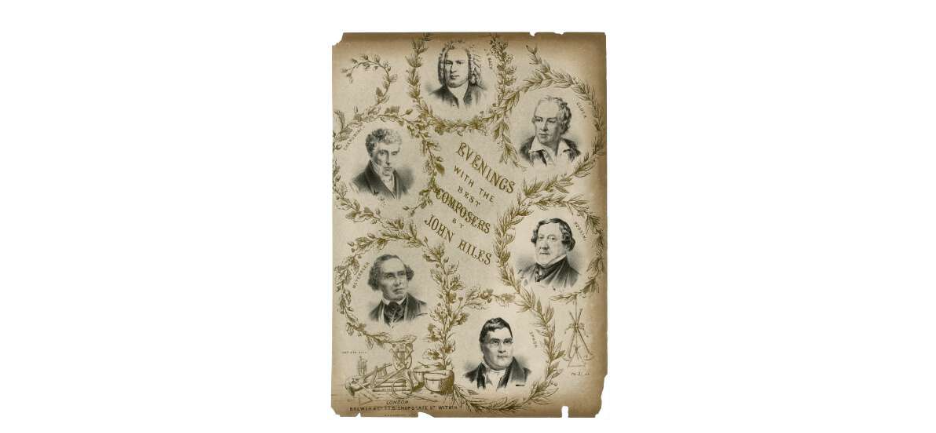

Brahms is of course a major composer, and very popular today. Spohr is not a well-known name to most people, so I want to start by giving some brief details of the man, his life and his legacy.

Louis Spohr was born in Brunswick, North Germany in 1784. To put this date in context, In Vienna Mozart was aged 28 and sadly had only 7 more years to live. Haydn was in full flow in Esterhazy, aged 52, and would live another 25 years. Beethoven was a lad of 14 living in Bonn.

Spohr showed early musical ability and was taken on by the Duke of Brunswick as a violin player in his orchestra at the age of 15. From that time on to the end of his long life he was able to earn a living as a player, conductor and composer. Unlike Mozart and Schubert he never had to starve in a garret. He married an 18-year-old harpist, Dorette Scheidler, in 1806 and they remained happily married until her death 28 years later. He composed 10 symphonies, several operas, 18 violin concertos, 4 clarinet concertos, many songs, 36 string quartets and a very successful octet and nonet. At the height of his fame some German critics hailed him as the natural successor to Beethoven, a claim that will seem somewhat ridiculous to us today but demonstrates how well he was regarded. He toured England on 3 occasions and was well received.

Cover sheet for ‘Evenings with the best Composers’, including amongst others, JS Bach, Gluck, Rossini and Spohr c. 1860 © The Trustees of the British Museum

He also invented the violin chin rest, the baton, and rehearsal marks for which orchestral players should be very grateful.

As a conductor he must have cut an imposing figure. He stood about 6ft 5 inches, and weighed about 18 stone

In 1808 he met Beethoven, and they worked together on Beethoven’s Ghost Trio. Spohr reported that the piano was out of tune and Beethoven’s playing harsh and careless. Later Spohr moved to Vienna and met regularly with Beethoven in coffee-houses and wine-bars. In Spohr’s biography Professor Clive Brown reports that Beethoven would regularly call in at Spohr’s apartment for tea on a Sunday afternoon when he was out for a walk. There he would play on the hearthrug with Spohr’s two young daughters – a delightful picture! It is very likely that Beethoven, who never managed to attract a wife, envied Spohr his cosy domesticity.

The sextet was written in 1848, when Spohr was 64. Not, then, a work of old age, (he died 11 years later in 1859 at the age of 75) but definitely a work of his mature years.

Audiences of the early 19th century always found Beethoven’s music a challenge to listen to. There were abrupt changes of key, strange dissonances, complex rhythms, novel orchestration. With Spohr, audiences were on more familiar ground – they felt safe. Critics, on the other hand, sometimes complained, particularly of Spohr’s later works, that his music did not progress and drew too much on earlier works. Audiences and critics frequently disagree. The conservatism that seemed a fault to critics was seen as a bonus to audiences.

Nobody knows why Spohr decided to use the sextet form for the first time at the age of 64 but he had always been keen to experiment with new formats – double quartets, a concerto for string quartet and orchestra, for example. The sextet offered him the chance to enjoy the extra sonority provided by the depth of 2 violas and 2 cellos.

1848 has come to be known for a series of revolutions that broke out throughout Europe with the aim of removing the old monarchical structures and creating independent nation-states. Spohr was a democrat and a free-thinker and welcomed this new thinking. No doubt he was inspired by the spirit of revolution as he composed the sextet. In fact, in the federation of states that would later become Germany, the revolution did not bring the hoped-for results in that year. But signs of a new order were on the wall. On the score of the sextet, Spohr wrote ‘Written in March and April, at the time of the glorious people’s revolution for the liberty, unity and greatness of Germany.’

The Dream of Worldwide Democratic and Social Republics – The Pact Between Nations, by Frédéric Sorrieu, 1848

(Note in this picture the German flag – black, red and gold – which first appeared in 1848 as a symbol of German national unity. ed.)

Despite the frisson of revolution in the air at the time, Spohr’s sextet is a beautiful, calm melodious work. Much to enjoy, nothing to shock. It is clearly the work of a composer who is not seeking to prove anything. He does not need to make a loud splash. Mendelssohn had died the year before and Spohr was widely regarded as the senior composer in Germany, a natural heir to Beethoven, rivaled only by the emerging Richard Wagner – a very different type of composer. Brahms had yet to emerge, being only 15 in 1848. Robert Schumann was sadly showing signs of the mental disorder that would kill him.

Spohr makes full use of the extra sonorities provided by the 2nd viola and 2nd cello. Many of his works contain very showy parts for the first violin (Spohr was a violin virtuoso) but here the opening theme of the first movement is played by the violas with the violins providing ornamental trills, very restrained and generally marked pianissimo. After this quiet beautiful first theme, we might expect the second theme to be a contrast, but it, too, is peaceful.

The second theme is equally melodious and serene. Nothing to frighten the horses. The whole work is remarkable for the fact that there are very few forte passages, and no fortissimo. It is also notable for a favourite device of Spohr’s, the fast descending scale decorated with trills – very difficult to play I am told!

The second movement is a tender larghetto, the third an elfin-like Scherzo and the finale is a joyous Presto.

The ‘glorious revolution’ was overthrown in Germany in 1848 and when Spohr was invited to perform in Breslau in 1849 the city was under martial law. Spohr rejected the invitation to perform, stating: “I would find myself unable to breathe, let alone to make music”. He finally made the visit in the summer of 1850 after martial law had been lifted and played the Sextet (perhaps thereby affirming his continuing belief in the principles of the revolution). A Breslau newspaper reported: “…that, at his present age [66] he plays with all the fire and energy of a young man and surmounts the greatest difficulties with amazing vigour and authority, is simply phenomenal; it has never happened before!”

Louis Spohr quartet concert. Note the double music stand.

The sound of life

It is safe to assume that when John Dowland – whose poignant ‘Flow My Tears’, in an arrangement for string quartet, we are playing in our forthcoming concerts – took up his post as lutenist and composer at the court of Christian IV of Denmark in 1598, he travelled by ship from London to Copenhagen. In a way, ports such as Copenhagen were the equivalent of modern day airports, making the world seem a smaller place.

In finding connections to distant shores in our current concert programme it is clearer than ever that ‘no man is an island’, to quote John Donne (a direct contemporary of Dowland.) Carl Nielsen, born on the Danish island of Funen in 1865 would have been very aware from a very young age of Copenhagen’s pivotal position in maritime connections to the wider world.

Nielsen said that ‘I do not enjoy composing music if I continue to do it in the same way.’ His music is certainly very stimulating to play. To say that it is an unpredictable ride might suggest that it is difficult to listen to or hold together coherently in performance but somehow he knows how to make it all work. As a violinist himself (in the Royal Danish Orchestra for a while) he had an inside knowledge of string playing and gained considerably from playing many pieces that stimulated his imagination.

He wrote his second string quartet in F minor mostly while he was spending time in Germany on a scholarship after he had officially finished his musical studies at the Copenhagen Conservatory. He relished the input gained at Leipzig, Berlin and Dresden and was particularly impressed by Wagner’s operas. It is possible to hear a very distinct echo of Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll in the slow movement of the quartet.

He was subsequently to forge his own very individual way unencumbered by the magnetic pull of Wagner. His music is clearly infused with the traditional music of his homeland and in this sense he clearly felt close to the aesthetic of Edvard Grieg, as this little excerpt from the Allegro scherzando shows:

There is definitely a cheeky side to Nielsen. With him at the helm you never quite know where he’s going to take you next but you wouldn’t want to miss getting on board his ship. As he said: “Music is the sound of life.”

A distant shore

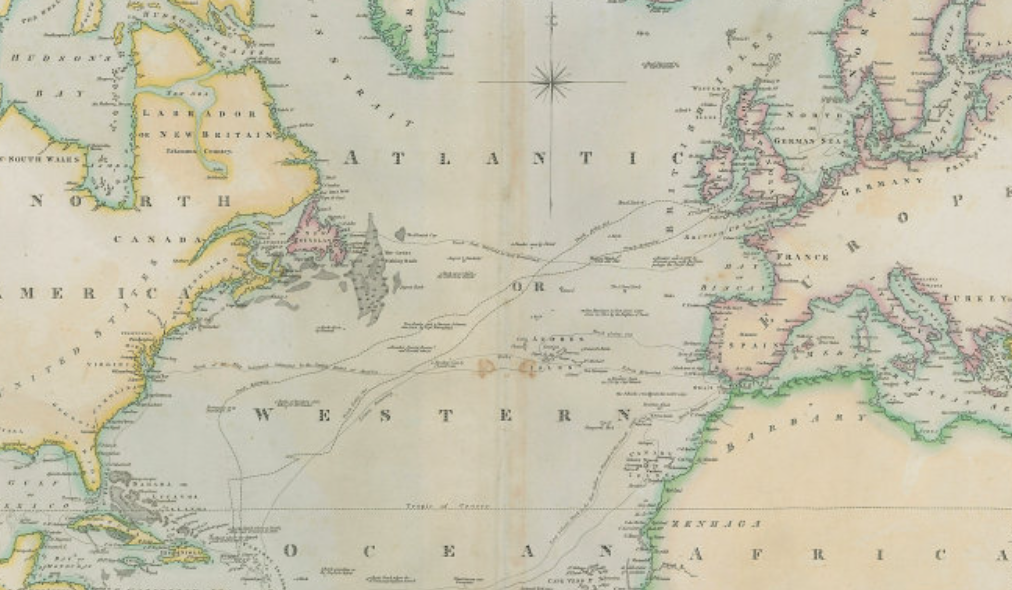

The contemporary composer Caroline Shaw lives on the east coast of the USA, in New York – a faraway shore from Topsham in Devon but as was mentioned in the previous blog post the trading connections between Devon and America are historically longstanding. This map shows the trading links – in particular the route to Newfoundland with its fishing riches.

As we will see, the connections across the sea are greater than a map can show.

Shaw was born in North Carolina, studied Suzuki violin with her mother and subsequently developed as much of an interest in singing as violin playing, although she has said that she has a particularly close affinity with the string quartet as she fell in love with the genre when she formed a quartet with friends at school. She has very diverse musical interests and has collaborated with musicians in a number of different genres. She is not easily pigeonholed.

One of the characteristics of Shaw’s writing is how she embraces older musical forms and weaves the old into the new, but without it being obvious or derivative. She uses it as a spark for her musical imagination. In this sense she is writing in a great tradition of course, along with many other illustrious composers.

Entr’acte, which we are playing, is a response to the minuet and trio of Haydn’s Op 77 No 2 quartet. In programming Entr’acte with chamber music by Dowland and Locke written long before Haydn established the string quartet as a genre to be reckoned with, it feels right that Haydn’s significance is implicitly acknowledged, especially as we then go on to play a work (Nielsen’s second quartet) that is so confident and unabashed in the genre.

There is one passage in particular that references Haydn. We play it here:

The passage (very brief) in the Haydn that she has used is between 1:08 to 1:13 in this recording.

You have no doubt noticed that we don’t always play actual notes but move the bow across the string making a rather breathy sound. Shaw has said that, along with her love of singing (and even her instrumental works have a vocal quality to them) she has a particular interest in breath. “I can say that in the last few years, I have become much more attuned to my love of hearing breath. Recently I was recording a project and the audio engineer had taken out a lot of the breath sounds of the voice of the singer, and that’s actually what I love.”

Gaps and silence are built into Entr’acte, contrasting with music often of wild energy. There’s something about this verse by the great American poet Emily Dickinson with its hyphen breaks and mention of waves and breath that reflects the lulls and energy in Shaw’s music – music that is hugely rewarding to play as well as emotionally involving for both listener and player.

The Waves grew sleepy — Breath — did not —

The Winds — like Children — lulled —

Then Sunrise kissed my Chrysalis —

And I stood up — and lived —

(From ‘Three times – we parted’ by Emily Dickinson)

Coming up: Nielsen’s at the helm – watch out!

A composer in ordinary

In our next programme we will be starting with music written long before the advent of the string quartet as we know it. The viol consort music of the early English baroque period in particular has a very strong affinity with the concept of the string quartet – four equal parts interacting and ‘talking’ together. It seems that as long as there have been chambers (as opposed to big halls), there has been chamber music.

Let me take you up the Exe estuary.

Topsham, Devon, in 1788, bustling with life and trade.

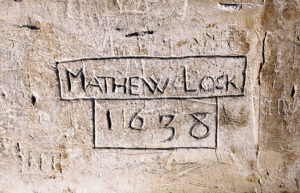

Topsham was a key port with strong trading connections to places as far away as The Netherlands to the East and Newfoundland to the West. A century and a half before this picture was painted a boy chorister at nearby Exeter Cathedral brazenly inscribed his name in the stone structure of the organ loft.

It is not known why he used this spelling. Maybe he was worried that the correct spelling, Matthew Locke, would have taken him too long to scratch in the stone; he might have got caught vandalising the building and have been severely punished. One wonders what he was doing in the organ loft anyway. I suppose he must have had to pump the bellows occasionally.

Locke’s tutor at Exeter would have been Edward Gibbons, brother of Orlando Gibbons. This curious little piece ‘What Strikes the Clocke?’ by Edward Gibbons, originally for three viols but here played on recorders, shows that instrumental chamber music had a place even at that time.

After his time as a chorister Locke broadened his vision considerably, travelling to the Netherlands and subsequently becoming ‘Composer in Ordinary to His Majesty, and organist of her Majesty’s chapel’ (Charles II and Catherine of Braganza.)

Matthew Locke

When Locke died, Henry Purcell, who clearly considered Locke to be something of a mentor to him, was moved to write an ode with the sentiment ‘What hope for us remains now he is gone?’ That is quite a tribute, from Purcell.

When I was studying in my first year at the Royal College of Music, I attended a lecture/demonstration given by Francis Baines, co-founder of the Jaye Consort along with his wife June. (The Jaye Consort was at the forefront of the revival of interest in the well informed performance of baroque music on instruments of the period.) Ostensibly it was a one-man introduction to the wonderful viol consort music of the early baroque but it started with him coming on to the stage seemingly with instruments hanging off him and he immediately enthusiastically demonstrated their particular characters. He was decidedly eccentric. He eventually sat down and started playing the viol, showing us how to produce the sound. He was talking enthusiastically about the harmonies and intervals in the music, which is often surprisingly dissonant. He got so involved in what he was showing us that he was overcome with emotion and excused himself saying that he couldn’t do any more and walked off the stage, instruments in hand.

That really cut it for me. I wanted what he had. A few days later I sought him out and he very kindly encouraged me to come along and join in the viol consort group that he was teaching. I attended these sessions for a while but couldn’t continue with them as I had to focus on my viola studies but I will always be grateful for all that he showed me and for the unforgettable experience of intimate communal music making that is at the heart of viol consort music and that resonates strongly in string quartet playing too.

The suite by Locke that we are playing is basically a set of dance movements. Here is the Courante. By the time we get to the concerts it will run even faster. And you will be able to see all four of us.

Next blog post: From Topsham to… New York. The transatlantic connection and the music of Caroline Shaw.

Behind the scenes

Greetings from Divertimento String Quartet.

Lindsay and I (Andrew) had injuries to our fingers quite recently that temporarily jeopardised our playing commitments. I had a bizarre altercation with a handle of a chest of drawers that left one of my fingers lacerated and Lindsay performed impromptu involuntary surgery on a finger tip while chopping vegetables. Fortunately our digits recovered just in time for us to be able to fulfill our playing engagements.

So, on the same theme of extra-musical behind the scenes trivia and in the spirit of seasonal story telling and merriment, we thought that we would share a few other pre-concert incidents that have happened over the years, just in case we have ever given the impression that our rarified artistic world is devoid of the experience of the mundane.

Mary:

I was playing in a concert with the English Chamber Orchestra. The soloist in the first half of the concert had been the violinist Frank Peter Zimmerman. We were chatting with him in the green room and then it was time to go back on stage for the second half of the concert. I couldn’t get my violin out of the case; somehow the lock had jammed. Frank Peter pushed his Strad into my hands and I hastened after the others to get on stage.

Every violin takes getting used to, but I enjoyed trying to control this amazing instrument. After the concert Frank Peter triumphantly held up my fiddle… as he had spent the time prising open the lock on my case with a knife that he had got from the restaurant.

Lindsay:

I could waste rather a lot of your time recounting numerous pre-performance ‘incidents’. For instance a waitress was divested of her work outfit because I turned up to play for a wedding without my concert clothes. Yes, people sacrifice their dignity for me for the cause of art.

I was booked to lead an orchestra in Plymouth and when I arrived at St Andrew’s church for the rehearsal I opened up my violin case to find nothing inside. This is a bit of a theme, I confess, and I am very grateful to my family for saving the day when I’ve not managed to get to a rehearsal on a concert day with an instrument to play.

Andrew:

Amongst other ignominious stains on my reputation, I offer this:

Concert day at The Royal College of Music. The Director, Sir David Wilcox and other big wigs were sitting in the gallery of the main hall awaiting the arrival of the orchestra on stage to play Brahms’s Serenade No 2 Op 16. This piece has no violins so the violas are very much in the spotlight.

As I got to the stage door to walk on with the other musicians it dawned on me that my music wasn’t on the stand – I had taken it home to practise it after the rehearsal earlier that day. I knew that I had brought it back to the College though. I told the conductor that I was going to get the music from my viola case. I discovered that the music wasn’t there. I realised that I must have left it in my locker – in another part of the large building. I informed the conductor of the situation. To get to the corridor where the lockers were involved going through the opera studio that was underneath the main hall – it still is, probably.

The floor had very shiny lino on the floor in the audience area of the studio and as I rushed through the room, I found myself skidding around the corners, not unlike the sliding movements of those professional tennis players on clay courts. When I got to my locker in the dark corridor I reached for the key in my pocket, searching, but in vain. I’d left it in my viola case.

I rushed back to the green room of the main hall, skidding all the way, grabbed the key and returned to the corridor, extricated the music and headed back, performing skating movements that Torvill and Dean would no doubt have been impressed by.

I arrived at the stage door breathless and flustered. The conductor, Michael Lankester, was surprisingly calm. I was thankful for this as the forthcoming ordeal of my arrival on stage was looming. I bit the bullet. It wasn’t exactly an entry greeted with tumultuous adulation. I seem to remember some rather feeble hand clapping. I tried not to think about the people in the gallery.

It is a really beautiful piece, that Brahms Serenade. I haven’t heard it since that day. I think that I need to revisit it.

Vicky:

At a recent DSQ concert, I forgot to bring the correct shoes to wear in the concert. A good friend of mine – also a cellist as it happens – was in the audience and when I mentioned to her my predicament, she said “I will go and get my spare pair from the car for you.” rushed off with only minutes to spare before the concert and I found they were much too big. I headed off down the aisle of the church but to my horror I could barely put one foot in front of the other, as the shoes kept falling off. I had to skate my way down the church, clutching my cello, trying not to lift them at all, a difficult feat (feet!). The situation made me and the others in the quartet collapse into helpless giggles. I managed with difficulty to climb onto the platform and was still trying to control myself, with tears rolling down my cheeks, when we started playing Haydn, which quickly sobered me!

Laughter is the best medicine. We hope that you all have jocular and good times over Christmas and the new year with your families and friends, whilst keeping safe at this very difficult time.

We are so looking forward to performing our next programme in the new year. We will be playing works written between 1596 and 2011 and finding connections between Devon, Denmark and North America across the seas.

Mary, Andrew, Lindsay and Vicky

(We are indebted to the late and great Hollywood String Quartet for the photo idea.)

Fun and games

I may have given the impression in the previous post that Haydn’s Op 76 No 4 is full of angst. Don’t let this put you off. There is lightness too. Everything is in balance.

It is a tricky game to play, but great fun. Haydn offers so much.

To be, or not to be?

Leopoldinentemple and English garden, Eisenstadt Palace by Albert Christoph Dies 1807, courtesy Eisenstadt Palace.

Haydn’s quartet op 76 no 4 (written c. 1798) is known as ‘The Sunrise’. Sunrise? It is not a nickname attached to the quartet by Haydn himself. It is very likely that the association arose because Haydn was writing his oratorio The Creation around the time that he was writing the quartet and some people saw a relationship between the opening of the quartet and the inspired depiction of sunrise near the beginning of the oratorio.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mc4DORlzLY4

And yet…this quartet surely begins not tentatively like the first inkling of morning light but with a matter of fact held chord over which the first violin sets off on a dreamy, rising melody. Basically the chord acts as a pause, over which the violin extemporises. A pause at the beginning of a piece! What is going on?

There are several pauses indicated by Haydn in Op 76 No 4 – nine in all, not including implied pauses like the opening chord. One in particular is most unusual:

It is at the end of the first section of the first movement, before the usual repeat is indicated, implying a proper break in the flow of music – a settling before re-establishing that opening chord. Sunrises don’t have pauses in my experience. There’s surely much more going on.

Looking at the opening a little closer: after the placing of the first pause-chord, the first note that the 1st violin plays is dissonant and this dissonance happens each time similar pause-chords appear in the piece.

After the first section is repeated, the pause-chord appears again, firstly in minor mood

followed by another pause-chord (after three shorter chords) that surely must be one of the darkest Haydn ever conceived:

Amidst much that is vibrant and energetic in this first movement, these moments of reflection seem particularly telling.

Haydn attended Viennese salons where Enlightenment intellectuals were present and he would have been very aware of the massive wind of change going on with the thinking around the Enlightenment and the march towards the ‘age of reason’. He was a Roman Catholic man of faith. It is said that he was very attached to his rosary and often felt inspired to compose once he had held it for a while and prayed. (If this rosary still exists, it must be worth a lot!) The relationship between reason and religion would have exercised the mind of such a sensitive and thoughtful person.

The pauses in the music induce thoughtfulness in the listener. ‘To be, or not to be?’ Haydn takes us to a place of questioning, perhaps possibility, even doubt, and sometimes there is disintegration, like disappearing into an abyss. This happens in the last movement of this quartet where the first violin gets stuck, unable to find a way out, lonely, almost losing its personality:

Does his music simply stem from his thoughtful, imaginative character or does it reflect the revolutionary and enlightenment storms sweeping through Europe at the time, putting everything into question? I suspect that it is all of those things. Today his music is as relevant as ever, drawing us in to the wonder of life and opening up existential questions that perhaps have no answers.

“A quartet, honey?”

Could there be anything better to do on your honeymoon than write a string quartet? I am sure that Cécile,

Felix Mendelssohn’s wife, did know what she was letting herself in for, marrying the foremost musical celebrity of that period (in Frankfurt, at the French Reformed Church, where her father was the minister – the building was sadly destroyed in the Second World War.)

They really did the honeymoon in style – seven weeks in the Rhineland and Black Forest in 1837. The Rhine, bearer of ancient myths and symbolic of the connection with the wider world must have helped to stimulate their romantic souls. Surely they also debated the relationship between their respective Lutheran (Felix) and Calvinist (Cécile) backgrounds, that would also have involved reference to J.S. Bach no doubt.

Somehow Felix found the time and focus to work on his string quartet in E minor Op 44 No 2. They had five children – not all during the honeymoon, I hasten to add. Ten years later, Felix was dead, completely at a loss after his sister Fanny’s sudden death. Cécile was to die of tuberculosis six years later than him, aged 36, her family torn by tragedy.

Cécile is remembered primarily as a helpmate for Felix, in rather passive terms, as if this is what was expected of her, and it is clear that this is the ideal norm of that time and society. We hear little about her views or interests. It is all about Felix.

The music speaks volumes though, of their love. The slow movement of the quartet in particular is a give away, just as this Song without Words written around the same time contains a decidedly intimate dialogue between high and low voice that becomes symbolically unified as the piece progresses: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4CEiVZMo9A

Another hugely significant woman in Felix’s life, Bella Salomon, had given Felix a copyist’s manuscript score of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion around 1824. The Mendelssohn family were Bach obsessed and even had original Bach scores in their possession but this close encounter with the St Matthew Passion so enthused Felix that it led ultimately to him undertaking a Bach revival, the legacy of which we still benefit from today. (I wouldn’t hold him solely responsible for Bach’s ‘re-discovery’. Amongst others, Mozart had already gone back to Bach and seen how very important he was. Mendelssohn’s particular mission was in reviving performances of Bach’s works.)

There is a passage in the last movement of the Op 44 No 2 quartet that shows very clearly how Mendelssohn is irresistibly thinking along Bachian lines.

In the context of the movement as a whole, it passes by without drawing attention to itself, which just goes to prove how totally integrated the profound influence of Bach was for Mendelssohn. Just as the Rhine was the central geographical current in the Mendelssohn honeymoon, musically Bach was Felix’s primary source of sustenance.

(Portrait of Cécile Mendelssohn by Eduard Magnus courtesy of Leo Baeck Institute)