Compared to many artists and musicians – Berlioz for example, or Mozart, or van Gogh – we know very little about the inner life of Johannes Brahms. He took great pains to dispose of any trail that would give anything away, even requesting of friends that they destroy evidence of correspondence from him. What we are left with is his music, which is surely as confessional as any words written in a letter, and tells us so much about him. Surely he was complicit in this manner of self-revelation.

“If there is anyone here I have not offended, I apologise”, he said when leaving a party. Amusing as it is, it shows how single minded he was. (That such irascibility may have been the result of sleep apnoea is by the by.)

By the time that Brahms composed his Op 18 string sextet in 1860, aged 37, he had written a large amount of music, including, it is believed, twenty string quartets. Most of this he had destroyed in a determined striving for what he thought was worthwhile, particularly in relation to the iconic musical forbears he so revered.

So this sextet was written, surprisingly, before his first official string quartet, Op 51 No 1. He needed time to find a way to form his own statement and response to the acknowledged supreme writers of quartet music – Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Although he learnt the violin when he was young, his primary instrument was the piano, and he was a piano teacher in the early part of his career. One of his pupils, Minna Völckers, recalled:

‘Between Friday and Tuesday I had to learn a study by Cramer, a prelude from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and the first movement of a sonata by Beethoven. That seemed to me to be an insurmountable task but it went better than I had imagined. I had to play him scales every time. He was very exact with everything and placed special emphasis on a loose wrist. Brahms could not be bettered as a teacher. He was gentle and kind, without praising much. I quickly made big strides with him. I really wanted to play some of his compositions, but hesitated to say so to him. My mother did it for me. “Yes”, he said, “the things are still too difficult, but I will play duets with her” and we had to work on his sextet Op 18, which we immediately got down to in the next lesson. I had to play primo, and we went through it very exactly, and my family were also delighted by the fine music. None of us could ever understand the stupid twaddle that one so often heard about him, that his music was confused. Sometimes, if I asked him, he played fugues after the lesson.’

Presumably the version of the sextet mentioned here would have been a piano duet version; this was common at this time, to make such works available for people to play in their homes if they had a piano, which was very likely.

Brahms gained a huge amount of understanding about string playing from two very significant violinists in his life; Joseph Joachim, considered to be the greatest violinist at the time and a lifelong personal friend of Brahms, and Ede Remenyi, who Brahms toured with giving recitals in 1853. Remenyi had Roma music in his blood and Brahms soon started to incorporate elements of this traditional music in his compositions.

The scherzo of the sextet op 18 has an exuberant energy to it that surely stems from this source of inspiration:

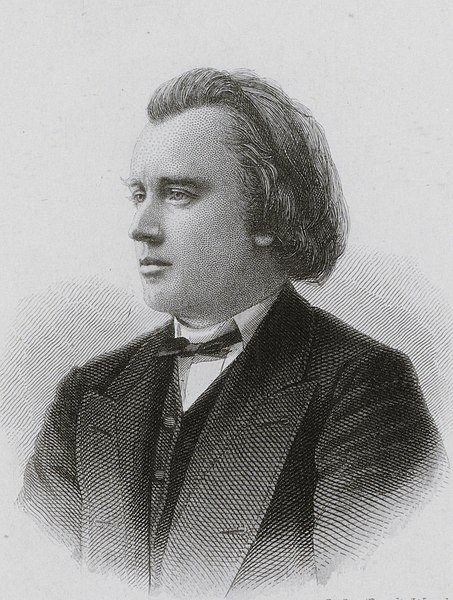

We are probably most familiar with photographs of the older, bearded Brahms. The younger version, as in the two portraits above, makes quite a different impression. It seems that, despite our impression of a very handsome young man, he was not a man brimming with self confidence. It is possible that his decision to break off his engagement to Agathe von Siebold was brought on by the unfavourable audience response to his first piano concerto and he felt that he would be an inadequate partner for her. He was also very close to Clara Schumann but this relationship did not become a permanent commitment.

Is there something fatalistic, or even funereal in this passage in the slow movement of the sextet, expressing resignation at his state of being?:

This excerpt shows well Brahms’s affinity with the richer darker tones of the musical spectrum that he found able to achieve with the help of the extra viola and cello in the sextet. The pizzicati of the violins provide a lovely touch, lightening the atmosphere a little. He knew just how to express his inner feelings in musical form.

Recent Comments