Oh to have heard Teresa Stolz sing!

Giuseppe Verdi, in his sixtieth year, was in Naples assisting in the production of his latest opera, Aida, when the lead soprano, Teresa Stolz became ill and everything was put on hold. Stolz (forty-one at the time) was his soprano of choice. (She performed the soprano solo in the first performance of his Requiem the following year – 1874.) His wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, had been a celebrated soprano too, but had retired. His first wife, Margherita Barezzi, had also been a singer.

Surely the voices of the women that he knew and his relationships with them fed his musical imagination. The same could be said of Mozart, for sure, and many other composers. It is as if there is something of these women (and men of course) embedded, almost recorded, in the music. Could this be, in a way, a hugely respectful and fond way of appreciating and celebrating them that lasts forever? A debatable subject, for sure, especially bearing in mind their varying roles and reputations in the drama, but something worth debating, perhaps.

Holed up in his hotel, the Grande Albergo delle Crocelle (favourite haunt of, amongst others, Casanova some time back), a beautiful spot by the sea, fifteen minutes walk from the theatre, Verdi must have been aware that there were some string players in the theatre orchestra with time on their hands and he proceeded to pen a large scale work for string quartet which had its first performance in the hotel. He was modest about its qualities but it is in reality an astonishingly assured and brilliant work, infused with operatic drama and ‘singing’ melodies.

Verdi was very involved in modernising opera theatre orchestras, or at least attempting to persuade theatre managers to change things. Opera orchestras had become, basically, large wind bands, and he pushed for more strings, particularly lower strings, to achieve a richer string sound that balanced with the wind instruments better. He (along with other forward thinking composers and academics) also insisted on changes in the layout of the orchestra because many opera houses had become stuck in eighteenth century layouts that didn’t reflect what was happening in operatic writing as it developed through the nineteenth century. He also requested a standard pitch of A = 435, which is a little lower than what is considered standard pitch today. His string quartet is an indicator of the standard of string writing and playing that he was trying to achieve. It is superb – and demanding – string writing, so clearly straight out of the opera.

Teresa was to remain a part of Giuseppe’s life to the end. After his wife died, Teresa went to live with him until his death. The exact nature of their relationship is not known. The story of their lives and loves could very easily be turned into an opera.

We are also playing a short piece for strings – Crisantemi – by Giacomo Puccini. Primarily an operatic composer, and one of the greatest composers ever working in that genre, he was moved to write this elegiac piece in a single night in January 1890, on hearing that his forty-four year old friend, the Duke of Aosta, had died of pneumonia.

Prince Amedeo had fought in the Third Italian War of Independence and was something of a national hero, having been wounded in the Battle of Custoza.

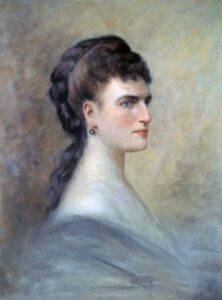

Clearly intended to show off his considerable assets, this portrait may have contributed, in an extraordinary turn of events, to him being chosen to be King of Spain from 1870 – 1873.

Having been installed as king, it turned out that the level of political turmoil in Spain at the time made his position unworkable and he decided to leave and head back to Italy. Still seen as a hero in Italy, his return was greatly celebrated. After his wife’s death, his second marriage was frowned upon by many, but his death, especially at a relatively young age, was a cause for national mourning. Puccini’s Crisantemi is tragic, tender and heartfelt, devoid of pomp or bombast. (It is believed that Madame Chrysanthème, a novel – published 1887 – by Pierre Lotti, about a young French naval officer who enters into a temporary marriage with a geisha while stationed in Japan, was partly the inspiration for Puccini’s Opera Madama Butterfly. The connection between Madame Chrysanthème and Crisantemi is potentially a very interesting subject, so far strangely unexplored and it is likely that it will remain that way unless a particularly inquisitive student reads this blog post and thinks that such a study would make a good subject for a degree.)

Amedeo’s life, and indeed the lives of those close to him, would also potentially make for for good operatic – or film material. We are available, as a quartet, to be part of the production – period costumes and all – and we would be happy to negotiate a fee for our services proportionate to the predictable huge success of the venture.

Recent Comments