Some years ago a scientific research group put out a request for antique objects, ornaments, artefacts, containing air that had been sealed in when they were made. The idea was that this air could be analysed for levels of pollution that existed in Victorian times, or whenever the object was made, in comparison with modern levels.

The sealed air makes me think of the silences in Haydn’s music. Surrounded and sealed by the notes around them, Haydn’s silences are pockets of silence from the 18th century. We are connected to the silence that he experienced and that listeners have experienced and will experience whenever the piece is played. It is also, for some, a communal experience of awareness of a greater universal silence, in the listening present moment of a performance. (In a way, the silence gives us a more authentic experience of the 18th century than the actual notes, because the sounds that we hear are the result of interpretation and such things as the sounds of the instruments and styles of playing, which have changed – but silence hasn’t.)

Haydn leads us to the silence, enabling it to grace our lives for a moment. Perhaps this is his greatest gift to us.

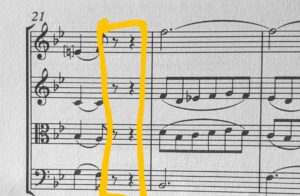

There is another striking silence in this quartet – if silence can be striking.

This one is particularly clever. It catches the players off guard – a deliberate banana skin moment when the music evaporates unexpectedly. Where has the music gone?! How are we going to get it back again? Silence rules. Everything comes out of silence and goes back into silence..

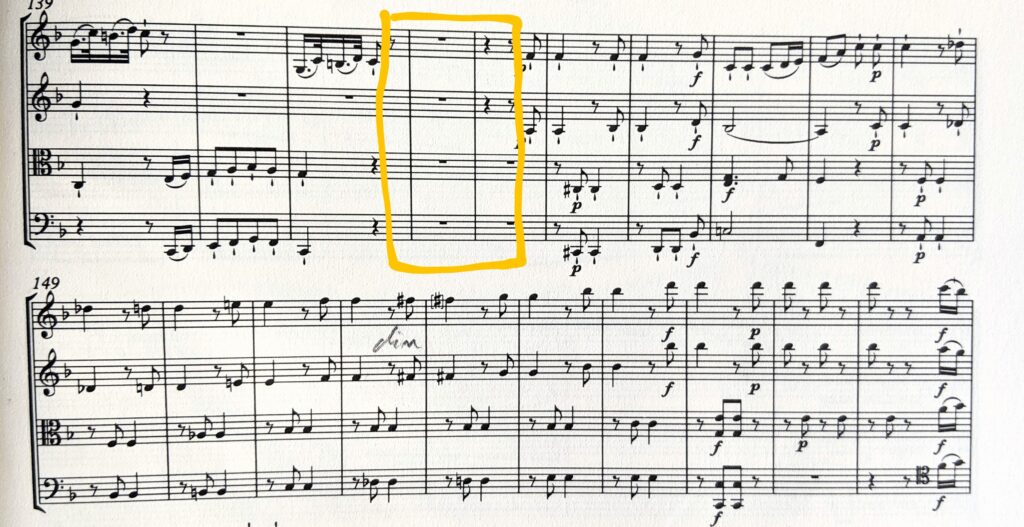

What follows this particular moment of silence is a passage of astonishing harmonic invention. It passes by quite quickly so here it is, slower.

Wagner – yes, Wagner!! – comes to mind. I would never have imagined it in Haydn. It just goes to show how original and modern Haydn was in his writing. With minimal means, Haydn breaks the bounds of the formal constraints of classical structures.

The more we play some pieces of music, the more they reveal themselves to us – and often the more mysterious they become. Could this be a definition of great music? It is certainly the way of Haydn quartets which, with seemingly simple resources, give us so much to ponder and enjoy.

Recent Comments